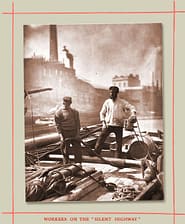

THOUGH so much has been said of late concerning our canal population, and the evils attendant on their mode of life, the men who have the more difficult task of conducting clumsy barges down the swift ebb and flow of the Thames, have been comparatively neglected. A long list of grievances may nevertheless be drawn up concerning this class. They have their faults and their hardships to expiate and to endure. Their former prestige has disappeared. The silent highway they navigate is no longer the main thoroughfare of London life and commerce. The smooth pavements of the streets have successfully competed with the placid current of the Thames: the “Merry Waterman’s” mission is exhausted, he is superseded by the trains, cabs, omnibuses, and penny steamers of modern London. He is compelled to abandon the pleasant occupation of rowing passengers to and fro, and must now devote himself solely to manoeuvring huge barges. Lightermen and bargemen have succeeded to the “Jolly Young Waterman,” immortalized in Dibdin’s ballad opera. Of course a few of the latter still find occupation, and notably below London Bridge, where they take passengers out to ships anchored in the stream; but when comparisons are established between the present and past demand for watermen, it may well be said that this means of earning a living has almost died out. Nevertheless, the old institutions which formerly governed the London watermen still exist, and possess considerable power. Indeed, this is one of the many anomalies in our social system which does not fail to produce considerable mischief.

Under Queen Anne’s reign it was probably both wise and proper to incorporate the watermen of the Thames in a company or guild, and grant them certain privileges. They alone were allowed to navigate the river; but, on the other hand, they were compelled to man her Majesty’s fleet in times of war. Now, by an Act passed by Parliament in 1859, these privileges and these obligations were abolished; but the Watermen’s Company still continued to exist, and to this day governs to some extent the navigation of the Thames, its jurisdiction extending from Teddington Lock to Lower Hope Point, near Gravesend. By the side of this old corporation a new authority, known as the Thames Conservancy, has sprung into existence, and also derives, its powers from Acts of Parliament. Thus the Thames is governed by two distinct authorities, each entrusted with a similar task; while, to further complicate matters, the lightermen have themselves created yet a third organization which is at times able to challenge both these bodies. I allude to the Trade Union formed by the lightermen.

A bargeman generally obtains his licence from the Company, but if refused, from the Thames Conservancy, while at the same time he relies on his trade union to maintain the rate of his wages and procure him employment. The masters, however, experience considerable difficulty in managing their affairs and executing the orders they receive with due punctuality, as they are thus exposed to the conflicts which arise between these various organizations. The working men are able to play the one off against tie other in their struggles to obtain exceptional terms from their employers.

The head of a city firm, owning a large number of barges, described all these difficulties to me, but was more particularly bitter in his complaints against the Watermen’s Company. This Company is governed by a self-elected court, or managing committee, and any one who has once become a member is obliged to remain associated with the society all his life. He is compelled to continue paying his quarterage, however dissatisfied he may be; and further to increase the income of the Company, the fines they have a right to inflict are generally heavier for the same offence than those imposed at a police court. Thus a master or a lighterman who has served his apprenticeship under the Watermen’s Company, and received his licence from them, must, in case of misdemeanour or infringement of any of their regulations, be brought before the Court of the Company and there sentenced. If he refuse to pay the fine imposed, he is brought before an ordinary magistrate who is compelled to enforce the verdict pronounced by the Company, and this without investigating the case at issue. The bargemen, on the other hand, who are licensed but are themselves not members of the Watermen’s Company, that is to say not “freemen,” are, it is urged, in a more fortunate position. They are summoned before an ordinary magistrate, when any accident or infringement of the regulations has taken place, and the magistrate often imposes a fine of one shilling in cases where the Watermen’s Company, anxious to increase their private funds, would inflict a penalty of £i. Though often excessively severe when a fine can be extorted, the Company is supposed to be less strict where money is not to be obtained. Thus, some months ago, an owner was fined £i because his name was not distinctly inscribed on his barge; at the same time one of he men was fined only ten shillings for sinking a craft worth £100. This disproportionate sentence evidently represented the paying capacity of the offenders rather than the gravity of their respective offences.

With regard to the character of the men who work on the barges, a graver accusation might be brought against the Watermen’s Company. Licences are sometimes granted to the most unworthy persons, and the safety of property on the river gravely compromised. I have a list before me of Freemen of the Watermen’s Company who have been sentenced to different terms of imprisonment for felony, for plundering barges, &c., and who have nevertheless again obtained the Company’s licence on their release from prison. One man, for instance, was tried in December, 1868, and sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment— Detective Howard convicted him of stealing wheat from a barge— yet this man is now working on the Thames with the Company’s licence. In October, 1869, another bargeman, denounced by Inspector Reid, was sentenced to fourteen years’ penal servitude, and I shall be curious to know, when this sentence is expired, whether the Watermen’s Company will renew his licence. The Company did not object to another man who had completed five years’ imprisonment, but gave him a licence, so that he was able to commit further depredations, for which he is now undergoing another term of seven years’ imprisonment. We also owe the capture of this thief to the same inspector of police. Then there is a man who was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment in May, 1870, who had previously been convicted on two occasions, and who is still working with the Company’s licence. In December, 1871, and in June, 1872, two men, also captured by Inspector Reid,were each sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, and are now both navigating the Thames with the Company’s licence. In December, 1873, three more bargemen were sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment each for felony, and in January, 1873, there was another similar conviction; yet all these men have been again armed with the Company’s licence, and can resume tranquilly their evil practices. Further, it is not always easy to refuse their services. For instance, my attention was directed to a case of an apprentice, who was condemned to ten days’ imprisonment for stealing locust beans. When he was released from prison, the Company, through whom he had been apprenticed, insisted that he should continue to serve his time, and fined the employer for refusing to entrust his goods and barges to a convicted felon. Nor has the employer any redress against this injustice. He must submit to the jurisdiction of the Company to which both the apprentice and himself belong. But if dishonest men are maintained in places of trust, one of our most important channels for the conveyance of goods, will become insecure and discredited.

There have been, unfortunately, some other convictions besides those which I have mentioned, and it really would seem as if the Company gave licences to work in a most blameworthy and indiscriminate manner, so long as the licence-holder pays his quarterage. The police state that these men go about armed with these licences and board crafts in the dead of the night. When arrested they allege that they were only anxious to ascertain whether any men not free of the Company were working on board the crafts in question. But if they are not detected, they seize such opportunities to plunder the barges, or to plan an attack, or to persuade the men in charge to help them.

At the same time, while the lack of uniform control, and perhaps the eagerness of the Company to secure quarterage fees, &c., have tended to corrupt the men employed in the navigation of the Thames, and facilitated the introduction of thieves within their ranks, I should be very sorry to cast a slur over the whole class. undoubtedly, many most honest, hard-working, and in every sense worthy men, who hold licences from the Watermen’s Company, or from the Thames Conservancy.

That these men are rough and but poorly educated is a natural consequence of their calling. Never stationary in any one place, it is difficult for them to secure education for their children, and regular attendance at school would be impossible unless the child left its parents altogether. Thus there is an enormous percentage of men who cannot read at all. Their domestic arrangements are, however, better than the canal bargemen. Cramped up in little cabins,the scenes of over-crowding enacted on board canal barges, equal and even exceed in their horrors what occurs in the worse rookeries of London. Fortunately, the very nature of their occupation compels the men to enjoy plenty of fresh air and invigorating exercise, and this naturally counteracts the evil effects resulting from their occasional confinement in cabins unfit for human habitation. It has also been justly remarked that these floating homes are the probable medium for conveyance of epidemics from bank to bank of the canals. But these remarks apply almost exclusively to our canal and not to our Thames population. As the barges on the Thames do not travel so far, it is easier for the men to live on shore, where of course they can obtain better accommodation, particularly if they are married and have families. Nevertheless, there is urgent need of reform to ameliorate the condition of bargemen, both from a sanitary and educational point of view. It is most revolting to think that in the narrow and dark cabins of a barge, children are sometimes born. The sun cannot shine within these cabin homes and purify the atmosphere; the germs of disease may therefore linger here for an indefinite time and be conveyed from place to place. Fortunately, this question has of late attracted considerable public attention several ardent reformers have taken the matter in ; hand, and sooner or later these good endeavours must bear fruit. We may, therefore, look forward to the time with some feeling of confidence, when the lightermen of London will be more worthy of the noble river on which they earn their living.

A.S.