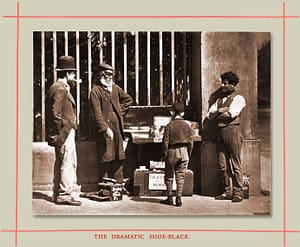

JACOBUS PARKER, Dramatic Reader, Shoe-Black, and Peddler, is represented in the accompanying photograph standing at his accustomed “pitch.” Although the career of Parker has been clouded, and his life-story is one of struggle and disappointment, yet he has fought the battle bravely, and, as a veteran, is not without his scars. “There is one thing I am proud of,” said Parker, one day; ” I am near three-score years and ten, have fought life’s battle and won, and will carry with me to the end its chief prizes-a hale heart and a contented mind.”1The quotations were jotted down as they were uttered. “Greed of gain, sir, has never been my motto. It is but a poor object to fill up every nook and cranny of a human heart from boy- hood to old age, as it does with many.” Again, in his own words, ” I have always advocated temperance and detested drunkenness! In my youth I never did apply hot and rebellious liquor to my blood, nor did, with unbashful forehead, woo the means of weakness and debility.’ Ah, sir, I have seen wine make woeful wrecks of men and women too, recalling the powerful lines, ‘ Oh! thou invisible spirit of drink, if thou hast no other name to go by, let us call thee Devil.’ “

” Rumty,” to use the cognomen by which Parker is known to a wide circle of poor friends and patrons, made a fair start in life. His father, he assures me, was a sort of private gentleman having some means at his disposal. One brother served his country in the army, another followed the law as a profession, while our hero was apprenticed to a wholesale stationer in the city, his father paying a premium to his master. Beyond this Parker appears to have received no further pecuniary aid, so that when he completed his term of apprenticeship he had to make his way in the world single-handed. At this point in his career he had a number of business associates, but the ties that bound them together were soon broken, and their paths diverged. Some he lost sight of, others he accounted least likely to succeed carved out their fortunes for themselves while he became a journeyman vellum-binder. In this capacity he obtained work in different parts of England, and at last succeeded in getting a post as vellum-binder in the Stationery Department of the Treasury Office. He held this position under the Government contractor for nearly twenty-two years: but to continue our narrative in his own words :—

“At this time, I may say, I lay in clover. Like all gentlemen who labour under the wings of Government, I enjoyed short hours, and a very fair salary. My hours were from about ten to four. I cannot say I was over provident, otherwise I might have saved a trifle of money. I strove, however blindly, to make the most of the present, by devoting my leisure to the drama. I became acquainted with a distinguished prompter in one of the London theatres, and forthwith entered upon an after-hour dramatic career, while still in the Treasury in 1846. I appeared in ‘ Green Bushes’ and’ St. George and the Dragon’ at the Adelphi, as a super, of course; but I soon rose to be St. Philip of Spain in ‘St. George and the Dragon.’ I must tell you I had previously appeared in Shakspearian characters at other theatres. But in Othello I came totally to grief, and quitted the stage for a term, until, indeed, I made the acquantance of the prompter. Another painful circumstance occurred. I had risen unaided to perform Hamlet’s ghost. It was a packed house, and somehow I made a fatal blunder m pronouncing one word. In place of saying The glow-worm shows the matin to be near,’ I said’The glow-worm shows the mating to be near.’ This was my first and last appearance as ghost, and you may be sure I got full credit for this original rendering of Shakspeare. I had my successes, too, I remember; one evening when the’ Mysterious Stranger’ was on, the gentleman who had to play the corporal on duty failed to appear. The manager was in a fix, until, at the last moment, I volunteered for his part. I had only a few words to say in addressing the dealer in forged passports, but it was a success. After that I became a dramatic reader, got myself up in Goldsmith’s ‘Deserted Village,’ and, in the costume of the period, personating Oliver himself. This brought me before many literary circles in different parts of London and its suburbs, but the pay was little better than that of a super.

“Suddenly I fell ill, lost the sight of my left eye, and had to leave my regular work at the Treasury. After partial recovery I went to Liverpool, to try my fortune there; but found no demand for my services as a workman or as a reader. Coming again to London I hoped to join my son, who was a bookbinder; this, too, proved a failure, as he, poor fellow, had a wife and young family to support. I felt I was a burden to him, and cleared out. Age, poor health, and feeble sight told on me woefully; there was work for younger and stronger men, and my one-sided experience in the Treasury had done me no good as a workman. At last, sir, from sheer necessity, I drifted into Lambeth workhouse. I have nothing to say against such public asylums; they are a great boon to those who cannot help themselves, and many a poor soul in this city would be in a sad plight but for their aid. It galled my proper pride, however, and it is painful for a man who has had anything like decent training to have to herd with worthless, profligate, and abandoned paupers. When I regained my strength I determined to try to earn a living by reading and reciting, as you will see from this card.”

The card in question was inscribed with the name Jacobus Parker, Dramatic Reader, accompanied by a quotation from the Parochial Critic, which ran thus :—

“June 6th, 1871.

“An inmate of Lambeth Workhouse, Jacobus Parker, well known to the guardians, has taken his discharge, and is trying to earn a living by reciting portions of Shakspeare’s plays. He has an excellent voice, capable of considerable modulation and expression. He is passing under the appellation of Jacobus Parker.”

“Although,” continued Parker, ” I was dubbed by my admirers, ‘William Shakspeare,’ I did not confine myself to the works alone of the great dramatist, but recited as well portions from Burns, Thomson, Bloomfield, &c. My chief successes were in the ‘Carpenters’ Arms,’ William Street, Kennington, where I have entertained many a gathering of my supporters. I still have what I call my Shakspearian cloak, and can give you, old as I am, a Shakspearian evening whenever you choose.

“Now, I am stationed as a shoe-black, at your service, armed with a peddler’s licence. I get along fairly well. My pride, perhaps, stands in my way; and were it not for the unsought kindness of my landlady I would fair badly at times.

“I occupy a little room, a garret, all my own, for which I pay half-a-crown weekly. I suffer some annoyance from the brainless practical jokes of a pack of loafers, who have respect neither for old age nor poverty. To tell you the truth, when I think of my past and present, I am surprised to find myself so happy and contented. My only care is to earn enough to carry me through to the close of each day. I have no bills to meet — no taxes save my licence — no burdens except old age, and that hangs lightly on my shoulders. I quite endorse the sentiment, ‘True hope ne’er tires, but mounts on eagle’s wings, kings it makes gods, and meaner creatures kings.’ Thank God, mean as I am, I am blessed with that princely inheritance, hope, and with what the wealth of kings cannot secure, contentment.

“I have not told you that I was mainly indebted for my rescue from the Workhouse to the kindness of the Ex-Premier, Mr. Gladstone. I wrote to him, and he replied at once to me, a pauper, in a manner so kind that ‘it brought my heart to my mouth.’ He also sent his secretary to inquire into my case, and the result was a prompt grant of £10 from the Queen’s bounty. This started me in the street, where I have since continued to earn a living.

“A shilling a day is about my average net profit ; on Sundays I make a trifle over. Sunday morning brings me sundry boots to shine. But if I could get a half- crown reading once a week, I would gladly cut the Sunday work. I am not above cleaning Christian boots on Sunday, yet I would fain rest from my labours.

“Should any of your readers want a Shakspearian evening, I will get my cloak repaired, and rest on the Lord’s Day.”

A.S.

- 1The quotations were jotted down as they were uttered.