STREET vendors of pills, potions, and quack nostrums are not quite so numerous as they were in former days. The increasingly large number of free hospitals, where the poor may consult qualified physicians, the aid received at a trifling cost from clubs and friendly societies, and the spread of education, have all tended to sweep this class of street-folks from the thoroughfares of London. Although of late years much has been done by private charities to supplement the system of parochial relief, there is still a vast field open for the extension of medical missions among the lower orders of the community. Far from being in a position to record the extinction of the race of “herbalists” and “doctors for the million” who practise upon the poor, my investigations prove they are still about as numerous as their trade is lucrative.

It would be unjust to say that the itinerant empirics of the metropolis have advanced with the age, as it is part of their “role” to adhere to all that is old in the nomenclature and practice of their craft. An intelligent member of the fraternity informed me that as members of the medical profession, they are bound to use what may be called “crocus” Latin. “Our profession is known, sir, as ‘crocussing,’ and our dodges and decoctions as ‘fakes’ or rackets. Many other words make up a sort of dead language that protects us and the public from ignorant impostors. It don’t do to juggle with drugs, leastwise to them that are ignorant of the business. I was told by a chum of mine, a university man, that ‘crocussing’ is nigh as old as Adam, and that some of our best rackets were copied from ‘Egypshin’ tombs.” I ventured to remark possibly they were inscribed on the tombs as a warning from the dead. “Like as not,” was the rejoinder, “I expect the dead in this country could tell us summat about poisoning by Act of Parliament. Pardon me, sir, you may be a licensed surgeon yourself. But I would as soon swallow a brass knocker as some of your drugs. A brass knocker is a safe prescription for opening a door, it’s poison as a pill. I believe it is just the same with the poisons took out of the bowels of the earth, where they should be left to correct disorders. Herbs are the thing, they were intended for man and they grow at his feet, for meat and medicine. You see, sir, I’m a bit of a philosopher; when I’m not ‘pattering’ — speaking — I’m thinking. I have been a cough tablet ‘crocus’ for nine years, only in summer I go for the Sarsaparilla ‘ fake.’ Sometimes this is a regular ‘ take-down ‘— swindle. The ‘Blood Purifier ‘ is made up of a cheap herb called sassafras, burnt sugar, and water flavoured with a little pine-apple or pear juice. That’s what’s called sarsaparilla by some’ crocusses.’ If it don’t lengthen the life of the buyer it lengthens the life of the seller. It’s about the same thing in the end. A very shady’ racket’ is the India root for destroying all sorts of vermin including rats. It’s put among clothes like camphor. Any root will answer if it’s scented, but this racket requires sailor’s togs; for the ‘ crocus’ must just have come off the ship from foreign parts. It also requires a couple of tame rats to fight shy of the root. The silver paste is a fatal ‘fake.’ The paste is made of whiting and red ochre. The ‘ crocus’ has a solution of bi-chloride of mercury which he mixes with the paste, and rubbing it over a farthing silvers it. He sells it for plating brass candlesticks and such like, but it’s the mercury that does the business, he don’t sell that. The mercury in time gets into his blood and finishes him. I have known two killed this way.

” There are many different dodges in ‘crocussing.’ One man I know, togged like a military swell, scares the people into buying his pills. He has half-a-dozen bottles filled with different fluids he works with, turnin’ one into t’other. He turns a clear fluid black, and says, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, this is what happens to your blood when exposed to the fogs of London. “Without blood there is no life !” You seem bloodless, my friends; look at each other.’ They look, and almost believe him. ‘Next to no blood is impure blood! This is your condition, I can describe your symptoms; I offer you the only safe, certain, and infallible remedy.’ This style of ‘ patter ‘ makes the pills fly, but it’s not everyone can come it to perfection.

“As to myself, my’ patter’ is on the scholarly tack; reason and persuasion. I uphold the medical profession for most things, and tell all I know, and more so, about Materia Medica, for I don’t know much. Once a learned cove, a student, I think, tried to take a rise out of me. Says he, ‘What’s Materia Medica?’ Says I, ‘If you’ve descended from Balaam’s ass, you’ve browsed on it in the fields !’ I never saw him again. I am not agoin’ to give you my (patter,’ I cant turn it on like steam. You should hear me at my best, it’s well worth publishing. On a fair night, in a good ‘pitch,’ with a crowd round me, my tongue seems aflame. Some of our best patterers’ lush heavily. One used to say ‘Demosthenes when he studied oratory, went to the sea-shore and filled his mouth with pebbles. I know a trick worth two of that, I go to the nearest public and fill my mouth with a glass of the best Scotch whisky.’ He went there once too often. The fact is, most of us come to the gutter through boozing, and if a racket is dishonest, you may be certain the ‘crocus ‘ drinks hard.

“The corn’ fake ‘ pays with a fellow who can’ patter.’ His stock costs next to nothing. It should be sulphur and rosin to drop on the corn red hot. But rosin does alone at a pinch.

“I find a good honest ‘racket’ pays best in the end, people buy and come again. I have had my regular customers for years, and now I make a tidy living both summer and winter, and I need all I earn, for I have my old mother depending on me. “

My informant has the reputation of being an honest, hard-working fellow. His cough tablets, if they do not possess all the virtues he ascribes to them, are certainly pleasant to the taste.

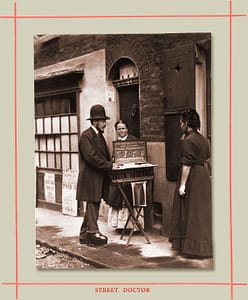

The subject of the accompanying illustration is a vendor of cough lozenges and healing ointment. He was originally a car-driver employed by a firm in the city, but had to leave his situation on account of failing sight. His story, told in his own words, is as follows:— ” First of all I had to leave my place on account of bad sight. It was brought on by exposure to the cold. Inflammation set in in the right eye and soon affected the left. The doctors called it ‘atrophy.’ I went to St. Thomas’s Hospital for nine months, to St. George’s Hospital, and to Moorfields Opthalmic Hospital. From St. Thomas’s Hospital I was sent to the sea-side at the expense of the Merchant Taylors’ Company. No good came of it all, and at last I was so blind that I had to be led about like a child. At that time my wife worked with her needle and her hands to keep things going. She used to do charing during the day and sewing at night, shirt-making for the friend of a woman who worked for a contractor. She got twopence-halfpenny for making a shirt, and by sitting till two or three in the morning could finish three shirts at a stretch. I stood at a street corner in the New Cut selling fish, and had to trust a good deal to the honesty of my Customers, as I could not see.

“At this time I fell in with a gentleman selling ointment, he gave me a box, which I used for my eyes. I used the ointment about a month, and found my sight gradually returning. The gentleman who makes the ointment offered to set me up in business with his goods. I had no money, but he gave me everything on trust. It was a good thing for both of us, because I was a sort of standing advertisement for him and for myself.

“I now make a comfortable living and have a good stock. When the maker of the ointment started he carried a tray; now he has three vans, and more than fifty people selling for him.

“I find the most of my customers in the street, but I am now making a private connexion at home of people from all parts of London. The prices for the Arabian Family Ointment, which can be used for chapped hands, lips, inflamed eyes, cuts, scalds, and sores, are from a penny to half-a-crown a box. Medicated cough lozenges a half- penny and a penny a packet.”

On the occasion of my last visit to my informant I had an opportunity of seeing one or two of his patients. One, a blacksmith, who had burned his arm severely, stoutly testified to the wonderful healing properties of the ointment. Another, also a worker in iron, came in to purchase a box: “It has been the saving of my wife,” he said; “she has a bad leg, but this salve keeps the wound open, and this wound do act as a safety-valve to her heart; were it allowed to close she would die of heart disease. Me and my wife discovered this, and it’s worth knowing. It draws off the bad humour, and, bless you, sir, there’s a deal of bad humour about my wife! I’m a temperance son of the Phoenix. My wife ain’t. She would not be a Phoenix if she could. She pulls one way, I pull t’other. She was teetotal for five years before me, but when I became a Phoenix she took the bottle. The Phoenix is a benefit and burial society. I pay three pence a week into it, and would be decently buried if I died. It is the interest of the Phoenix to get us to live long, and for that reason it is a teetotal brotherhood.”

This man was subscribing twopence halfpenny weekly to a club which secured for him and his family the attendance of a surgeon in the neighbourhood. For all that, he had sought the aid of this dispenser of quack compounds, and expressed himself perfectly satisfied with the result of his treatment.

I found in the course of my inquiries that the poor, many of them, prefer either resorting to quack remedies or employing their own paid surgeon, to placing themselves in the hands of the parish doctor, or under hospital treatment. This is accounted for in two ways. An honourable feeling of independence deters the poorer orders of the labouring classes from seeking parish relief in any shape. Others, who would gladly avail themselves of free medical advice, cannot find time to obtain a certificate from the relieving officer, and to present the certificate in the proper quarter. When all the forms have been duly complied with, grievous delays frequently occur in obtaining advice, and the necessary prescriptions; the latter have, in some instances, to be taken to the dispensary at the other end of the parish. Some of the aged, infirm, and friendless poor, who receive regular out-door relief, have under ordinary circumstances to pay a messenger a shilling for collecting their weekly pittance of half-a-crown. In time of sickness, when they cannot crawl from their door, they too are fain to avail themselves of the remedies of itinerant doctors.

A.S.