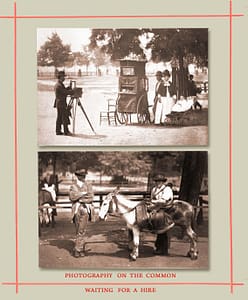

HOLIDAYS and idle days are golden days to nearly all who earn their bread in open spaces, thoroughfares, or streets. When ordinary business is at a stand-still, when the cares of commerce are laid aside for a few hours, and the great majority of the population seek to enjoy a little rest or recreation, the poor of London make their appearance, invade all places of public resort, and expect to reap a golden harvest from the holiday. Sundays, and especially Good Fridays, are often the busiest days in the year to many who seek to gain a livelihood out of doors. The parks, commons, gardens, in fact all pleasure-grounds, are overrun with eager caterers to the public. They offer for sale objects of the most modest description; but on such occasions the worst oranges, suspicious sweets, faded flowers, and the dingiest of ornaments, find comparatively speaking a ready sale. Clapham Common is of course one of the most accessible rendezvous for these itinerant vendors; but certain industries are more particularly successful on this spot. The place is especially attractive to itinerant photographers. During the season they flock to the Common; though the demand for the class of portrait they produce is of so constant a character, that one photographer at least has found it worth his while to remain in the neighbourhood even during the winter. This faithful frequenter of Clapham Common will be recognized in the accompanying illustration, and he is there represented engaged with the class of subject which generally proves most profitable. Nurses with babies and perambulators are easily lured within the charmed focus of the camera. They are particularly fond of taking home to their mistresses a photograph of the child entrusted to their care; and the portrait rarely fails to excite the interest of the parents. Nor does the matter rest here. The parents are often so satisfied that the nurse is commissioned to obtain one or more likenesses on her next visit to the common. Thus practically she becomes an advertising medium, and the photographer generally. relies on receiving more orders when he has once secured the custom of a nurse-girl. It need scarcely be remarked that at Clapham Common there are not only a large number of nurses and children, but these are generally of a class which can well afford the shilling charged for taking their likeness.

Success depends, however, more on the manners than on the skill of the photographer. Many practised hands, who have highly distinguished themselves in the studio, when the work is brought to them, are altogether unable to earn a living when they take their stand in the open air. They have not the necessary impudence to accost all who pass by, they have no tact or diplomacy, they are unable to modify the style of their language to suit the individual they may happen to meet, and they consequently rarely induce anyone to submit to the painful ordeal of having a portrait taken. On the other hand, men who are far less skilled in the art often obtain extensive custom by the sheer force of persuasion.

Example, also, is contagious, and if in a throng of people, one person ventures to step forward, others soon follow his example, and this renders the large gathering on holidays doubly advantageous. Thus, I know of one photographer, who obtained on Clapham Common no less than thirty-six shillings in the course of one hour. This, however, was altogether an exceptional circumstance, and a receipt of ten shillings a day is considered very fair for the common. Out of this sum about a quarter should be deducted for general expenses; and the work is not always pleasant. The photographer dare not leave his apparatus, for it is impossible to guess when a subject may present himself. He must stand for hours on the damp earth, idling away his time, when perhaps just as his patience is giving way, a tradesman’s cart will pull up, and his services are requisitioned to immortalize by his art the waggon which conveys groceries to the prosperous bourgeoisie of Clapham.

With the exception of gala days, the photographers on Clapham Common lead a somewhat humdrum life, for men who, in comparison at least, possess superior intelligence. Many, indeed, have held higher positions, have been tradesmen, or owned studios in town ; but, after misfortunes in business or reckless dissipations, were reduced to their present less expensive and more humble avocation. When the season which, for the frequenters of the Common, lasts from March to Whitsuntide, is over, the photographers, for the most part, hasten to popular sea-side resorts or follow the vicissitudes of the turf. During the month of March, their receipts on the Common rarely exceed 7s. per day ; but, during the warmer months, they often make double and three times as much. Those, however, who have the energy to attend at the races, to get up at five in the morning to catch the cheap train, who do not object to being locked up by the police under the Vagrancy Act if they are unable to procure a lodging, or who can pay 8s. for the privilege of sleeping in a tap-room, may hope to make large sums. The highest patrons of the turf are also the patrons of these itinerant photographers. The Prince of Wales, Lord Vivian, Sir Arthur Chetwynd, the late Marquise of Hastings, the celebrated horse-owner, Mr. Chaplin, and many other equally well known amateurs of horse-racing, have, I was most emphatically assured, all graciously allowed their portraits to be taken by these enterprising photographers. Considering the difficulties of reaching the race-course, the charge is consequently greatly enhanced ; the photograph of a break, trap, or coach bearing five persons is generally sold for £1. The Duke of Beaufort, for instance, always paid £1 for one photograph, and 10s. for the second portrait ; but the Prince of Wales, it appears, is renowned for his stubborn adherence to a fixed price. One of the photographers in question informed me that his Highness gives £1 for one photograph-“it is his sovereign price; and if an attempt is made to take another likeness he only orders the police to send you away.” On further inquiry, I found this gossip confirmed by more than one witness. Other sportsmen are particularly generous when it rains; and it seems as if this fashion of patronizing photographers on the race-course is really but charity in disguise. The ordinary glass pictures paid for so liberally are generally given over to the coachman, thrust into the rumble, and never see the light of day again. But the photographs taken on such places as Clapham Common, or at the corner of some quiet suburban street, meet with a more worthy fate. They are cherished in the homes of the poor, and are often found in the nurseries of the wealthy. They serve to recall the past, to revive latent affection for the absent; they never do any harm and sometimes awaken the better and more tender instincts of our nature.

By the side of the photographer, stands the donkey-boy, who also derives special benefit from the close proximity of Clapham Common. He lives in a slum hard by, and belongs to that peculiar and distinct race known under the generic term of costermongers. There are, I am assured, but two proprietors who let out donkeys for riding on Clapham Common, Mr. Carter and Mr. Laurence. The former has by far the most important business, and as many as twenty or twenty-five of his donkeys may be seen out on the common. The photograph, however, portrays Mr. Laurence’s son, leaning affectionately over his dumb companion, and a labourer, temporarily out of work, who has volunteered to assist him in his charge, and is evidently enjoying the sport. As a rule, the donkeys are bought at the beginning of each season, the female being invariably preferred, firstly, because its jolt is not so objectionable, and secondly, because, being generally in foal at the end of the season, it can be sold with a view to providing asses’ milk, for a higher price than it· cost. Eighteenpence per day is supposed to suffice for the keep of a donkey; but the income derived from the hire varies considerably, amounting on Good Fridays to £1 and even £1 10s., and falling at times as low as 4s. The ideal average is 10s. per day,and the true average probably a little less. It depends, however, who attends to the business, and one man driving two donkeys can make more out of each than what is derived from a greater number entrusted to the care of small boys. These latter generally receive a shilling per day, and are naturally apt to neglect or miss opportunities of obtaining a fare. If, however, the owners would content themselves with sure but smaller profits, they would find many ladies in the neighbourhood ready to pay 5s or 6s. per day to secure the exclusive use of a donkey for their children, and would also treat it with kindness. One lady even paid 4s. during all the winter months so that her favourite donkey should not be sold, but reserved for her children to ride again at the earliest dawn of spring.

Altogether it will be seen that the commons and open spaces in and about London, are not merely useful in maintaining the health of the population, and as affording some space for recreation; but they also open out new fields of industry for those who earn their living out of doors. On the great holidays, the itinerant street vendors crowd to the Common, and are able to breathe fresh air while still pursuing their ordinary avocations. Thus many wretched and forlorn individuals are induced by the ordinary interests of their business to occasionally imbibe the purest, most effective, and natural of tonics-a little oxygen; while those who are always on the Common benefit to a greater extent and boast of exemplary constitutions. Under such circumstances, I cannot help urging in conclusion, that all Londoners owe a deep debt of gratitude to those patriotic citizens who have combined and subscribed to defend the commons against the illegal and selfish encroachments of the neighbouring landowners.

A.S.