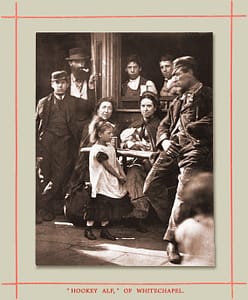

ON the 25th of October, 1693, Lady Wentworth sold a waste piece of ground, situated out in the fields to the east of London, on which a tavern or inn was forthwith built, and there it stands to this day, obtruding itself in a most remarkable manner in the very centre of the Whitechapel Road. Like an island in that great stream of human activity, the artery which stretches from east to west through the metropolis, this old inn has withstood all alterations, and remained unmoved by the huge suburb which has sprung into existence around. The road, the broadest road in London, had perforce to be narrowed here; for the sacred rights of property could not be menaced, and the inn was allowed to remain blocking the very middle of the thoroughfare. Nor has age and the conversion of the neighbouring fields into a crowded portion of the metropolis entirely deprived the inn of its former rural aspect. There are still tables and benches placed outside, as if to entice Londoners to sit and enjoy the country air, though they are no longer planted on the green sward, but stand on the hard and smooth pavement stone. Even new paint and a new roof have failed to destroy the quaint look of this inn, while the groups generally seated outside contemplating the broad, busy road before them, add to the interest of this resort. No public-house could have a better claim to be included within the scope of this book. It is essentially a street public-house, for it stands in the middle and not on the side of the street. Here the customers are allowed to drink in the open air, and a large proportion of the persons who profit by this opportunity are themselves dependent on the streets for their livelihood. The groups, however, that may thus be observed seated outside the inn are not always picturesque or pleasing, though generally interesting. There is a metropolitan mixture of good and evil in the countenances that may here be studied, which will supply food for thought, if the thought be not always cheerful. Thus in the photograph before us we have the calm undisturbed face of the skilled artisan, who has spent a life of tranquil, useful labour, and can enjoy his pipe in peace, while under him sits a woman whose painful expression seems to indicate a troubled existence, and a past which even drink cannot obliterate. By her side, a brawny, healthy “woman of the people,” is not to be disturbed from her enjoyment of a “drop of beer” by domestic cares and early acclimatizes her infant to the fumes of tobacco and alcohol. But in the fore-ground the camera has chronicled the most touching episode. A little girl, not too young, however, to ignore the fatal consequences of drink, has penetrated boldly into the group, as if about to reclaim some relation in danger, and drag him away from evil companionship. There is no sight to be seen in the streets of London more pathetic than this oft-repeated story the little child leading home a drunken parent. Well may those little faces early bear the stamp of the anxiety that destroys their youthfulness, and saddens all who have the heart to study such scenes. Inured to a life crowded with episodes of this description, the pot-boy stands in the back-ground with immoveable countenance, while at his side a well-to-do tradesman has an expression of sleek contentment, which renders him superior to the misery around.

The most remarkable figure in this group is that of “Ted Coally,” or “Hookey Alf,” as he is called according to circumstances. His story is a simple illustration of the accidents that may bring a man into the streets, though born of respectable parents, well trained and of steady disposition. This man’s father worked in a brewery, earned large wages, married, kept a comfortable home, and apprenticed his son to the trunk-making and packing trade. The boy frequently helped to affix heavy cases to a crane, so that they might be lowered from the upper story of a warehouse into the street. As the boxes were lined with tin it required considerable strength to push them out of the loop-hole over into the street, and, the young apprentice having inherited his father’s stalwart form, was selected for this work. On one occasion, however, he threw the whole of his weight against a huge case which, through some mistake, had not been lined with tin; of course the case yielded at once to so tremendous a shock, it swung out into the street, and the lad, carried away by his own unresisted impetus, fell head foremost to the pavement below. This accident at once put an end to his career in the trunk and packing trade, and rendered all the expense of his apprenticeship useless. He recovered, it is true, from the fall, but has ever since been subject to epileptic fits.

Finding that under these circumstances he could no longer attempt complicated and difficult work, he thought he would seek to make his living in one of those occupations where mere muscular strength is the chief qualification required. Thus he was able for some time to earn his living as a coal porter, and most fortunately made himself very popular among the “coal-whippers,” &c., with whom he associated. But even in this more humble calling fate still seemed to conspire against him. While high up on an iron ladder near the canal, at the Whitechapel coal wharfs, he twisted himself round to speak to some one below, lost his balance and fell heavily to the ground. Hastily conveyed to the London Hospital, it was discovered that he had broken his right wrist and his left arm. The latter limb was so seriously injured that amputation was unavoidable, and when Ted Coally reappeared in Whitechapel society, a hook had replaced his lost arm. Thus crippled, he was no longer fit for regular work of any description, and having by that time lost his father, the family soon found themselves reduced to want. “Hookey Alf,” as he was now called, did not, however, lose heart; and, pocketing his pride, he wandered from street to street in search of any sort of work he could find. Hovering in the vicinity of the coal-yards he often met his old fellow-workers, and whenever a little extra help was required they gladly offered him a few pence for what feeble assistance he could render. Gradually he became accustomed to the use of his hook, and proved himself of more service than might have been anticipated; but, nevertheless, he has never been able to secure anything like regular employment.

He may often be found waiting about the brewery in the Whitechapel Road, where ten or twelve tons of coal are frequently taken in during the course of the day. “Hookey” stands here on guard, in the hope that when the coal arrives there will be some need of his services to unload. On these occasions he will earn a meal and a few pence, and with this he returns home rejoicing. But, if after a long day’s patient endeavour he fails to make anything, the worry and disappointment will probably cause an attack of epilepsy, and thus add ill-health to poverty. The tender concern of his mother cannot soothe the wounded feelings of the strongman. The energy and will are still there, it is the power of action alone that is wanting; and this good-natured, honest man, feels that he ought to be supporting his mother and sister, while in reality he is often living on their meagre earnings. The position is certainly trying, and it is difficult to make poor “Hookey” understand that an epileptic cripple cannot be expected to fulfil the same duties as a man in sound health. It is some consolation to this worthy family to know that reliance may be placed on the daughter, whose earnings as a machinist keep the wolf from the door; but the spectacle of this once fine boy, the pride of his native street, now helpless in his spoilt manhood, must be a source of constant grief and disappointment. Perhaps the lowest depths of misery were reached when “Hookey,” in despair, slung a little string round his neck to hold in front of him a box or tray containing vesuvians, and presented himself at the entrance of a neighbouring railway station, and sought to sell a few matches. For a man still young in years, if not in suffering, this must have been a galling trial, and from my knowledge of the family I feel convinced that they keenly realized all its bitterness. “Hookey’s” misfortunes will, however, serve for one good purpose. They demonstrate that even those who resort to the humblest methods of making money in the streets are not always unworthy of respect and sympathy.

Many cases of this description might be found ” Whitechapel way,” by those who have the time, energy, and desire to seek them out; and personal investigation is at once the truest and most useful form of charity. It will always be found that those who have the best claim to help and succour are the last to seek out for themselves the assistance they should receive. It is only by accident that such cases are discovered, and hence my belief that time spent among the poor themselves is far more productive of good and permanent results, than liberal subscriptions given to institutions of which the donor knows no more than can be gleaned from the hurried perusal of an abbreviated prospectus. In this manner Dickens acquired his marvellous stores of material and knowledge of the people. Exaggerated as some of his characters may seem, their prototypes are constantly coming on the scene, and as I talked to ” Hookey” it seemed as if the shade of Captain Cuttle had penetrated the wilds of Whitechapel.

A. S.