“Tickets” comes straight from “the centre of civilization” and is a Parisian pur sang . He began life in the capacity of a linen-draper’s assistant, in the Rue de la Chaussee d’Antin; but, though working in so fashionable a quarter, he was subjected to the grinding exactions which render the French bourgeois so unpopular, and social revolutions of so frequent occurrence. His employer made him work from eight in the morning till ten in the evening, and only allowed him a half-holiday on Sunday afternoons. For all remuneration “Tickets” received questionable board and lodging, and the munificent sum of sixteen shillings per month. It is not surprising that under these circumstances his somewhat adventurous spirit rebelled against so monotonous an existence, and in despair he finally joined the army as a volunteer. Though the French soldier vegetates in a condition of proverbial poverty, “Tickets” might have remained contentedly in the army all his life; but, after eighteen months’ service, he was discharged on the ground of ill-health. It therefore became necessary for him to make a third start in life. He then tried his hand at agricultural work, and, as a farm-labourer, contrived at least to recoup his health; but this style of life was as monotonous and scarcely more advantageous than his previous existence behind the counter of the linen-draper’s shop. He was, therefore, only too pleased to avail himself of his father’s assistance to emigrate. With many blessings, tears, and a few gold pieces, supplied by his parents, “Tickets” embarked at Bordeaux for New York. I need, however, hardly remark that he found it nearly as difficult to obtain employment in the capital of the States as in Europe; and after a month’s useless endeavours he proceeded to San Francisco, via Panama. Here better fortune attended his efforts. After a fortnight’s search, just as he was on the point of parting with his last gold coin, he was engaged to wash the dishes at the Miner’s Restaurant.

Though this was scarcely an exalted calling, he nevertheless earned his board and lodging, and thirty dollars per month. It was a decided improvement on his European experience; but the work was dirty, and otherwise objectionable. Awaiting, however, his opportunity, he profited by the first vacancy to present himself as candidate for the important post of waiter at the same hotel, and during six months he served the Californian miners with the huge portions of green corn, waffles, hominy, and other dishes favoured in the Far West. A better post was now offered to him as courier and interpreter on a San Francisco and Sacramento line of steamships, where his knowledge of English, French, and German proved of good service.

It seemed, however, as if “Tickets” could never settle down to anyone distinct line of work, for in nine months’ time he was engaged in the new capacity of private night- watchman over a warehouse, for a salary of $40 per month. Then again, a little later, his employer no longer requiring his services, “Tickets” migrated to Chicago, where he was raised to the dignity of Professor of French at a school, and enjoyed the munificent stipend of $50 per month. But he had not yet reached the zenith of his career. Employment, with a salary of $60 per month, was offered him as book- keeper and interpreter in an hotel at New York, and here, at last, the hero of this chapter seemed content with his fate, and remained faithful to his new task for two whole years. Unfortunately, nostalgia, fatal to so many emigrants, is more particularly disastrous in its effects on Frenchmen. New York seemed provokingly near to Europe, and Europe meant Paris and the Boulevards. “Tickets,” after some years of prosperity, had saved money, and finally he stepped on board a Cunard steamer, and, long before he had realized his imprudence and appreciated his folly, he was landed at Queenstown. From thence to London was but a matter of a few hours, and here he arrived just in time to meet the great exodus of Frenchmen flying to our shore to escape the poverty and political persecution afflicting the mother country.

On all sides “Tickets” was warned not to return to France, where the War and the Communal insurrection had destroyed all chance of obtaining employment. Had he possessed more foresight and a truer knowledge of the difficulties of his situation, he might have attempted to return to the States while he still possessed the means of paying the passage; but he hesitated, and indecision, as usual, proved fatal. His savings were soon spent, and “Tickets” found himself in the most forlorn of all positions, that of a penniless stranger in this huge wilderness called London. Unprotected by friends or recommendations, he was treated with suspicion by every one, and his solicitations for work elicited no response. At last he was compelled to leave his modest lodgings for the still cheaper accommodation of a common lodging-house.

The first money”Tickets” ever contrived to earn in London was obtained from the manager of a theatre where he appeared as a “super” for the ordinary pay of a shilling a night; but, as he had now been reduced to that stage when daily payments are an absolute necessity, he had to give twopence interest on each shilling to the foreman, who paid him every evening instead of once a week. This extortionate interest is frequently imposed by the foremen who manage the” supers” at the various London theatres. Sometimes he was given prospectuses to distribute in the streets, and received in payment two shillings a day; but the work was very irregular. On other occasions he attempted to sell maps of London, but he was not well enough dressed. When he entered offices to show the maps he was condemned to a bad reception, by reason of his dilapidated appearance; and ultimately abandoned this work as hopeless.

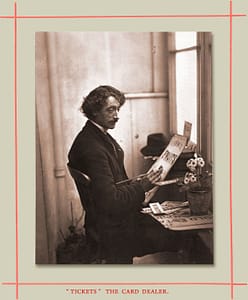

About this time “Tickets” made the acquaintance of a Frenchman who possessed considerable skill as a sign-painter; and the two forthwith entered into partnership. The one paints, the other undertook to travel. “Tickets” is the traveller. From morning till night he wanders about, looking into the windows of small shops, till he discovers a ticket of dingy appearance, stained in colour, dog’s- eared, bent, and altogether disreputable. ·With eagle eye all these defects are discerned, and “Tickets” enters boldly into the shop, to press on the tradesman the advisability of purchasing a new ticket. He undertakes to supply a precise copy of the old and worn announcement on a better piece of cardboard, freshly painted, or, perhaps, more elaborately ornamented. But the tradesmen do not respond readily to these offers. The small linen-drapers are perhaps his best customers, as they constantly want tickets with “Only Is. 11d.,” or “Cheap,” or, again, “The latest novelty,” inscribed thereon, and destined to be affixed to the soiled, dear, old, and waste stock, which must be sold to ignorant and deluded purchasers. These tradesmen must of course be approached with considerable care. On Fridays and Saturdays they are far too busy to listen to such solicitations, and “Tickets” prudently awaits till the beginning of the week, when they are less occupied, selecting in preference the morning. On the other hand, common eating-houses are more assailable in the afternoon, after the dinner-hour. Here there are tickets such as “Try our own dripping at 6d. a lb.,” or, “A good dinner for 8 pence,” &c. The steam, the grease, the close atmosphere of such establishments soon tarnish these cards, and “Tickets” has enjoyed many opportunities of announcing to the world the price of dripping in clean new letters. The price charged for an ordinary card is generally a shilling, each letter measuring two or three inches in size. The money is thus divided :- “Tickets” gives his associate 4d. for painting the card; but he supplies brushes, colours, ink, cardboard, &c., and this he estimates generally at a cost of about 3d. There remains, therefore, a profit of fivepence, to remunerate the trouble and time spent in getting the order. Of course there are many cards that cost more than a shilling, but the division of the benefits is generally maintained in about the same proportion. “Tickets” declares that if his associate had several travellers seeking for orders, and, if he were fully employed from morning till night, he might earn nearly twenty shillings a day at the above rate of remuneration, the chief difficulty being to get the orders. Even while reserving 5d. in the shilling, “Tickets” has never made more than fifteen shillings in a week; eight to ten shillings is the most usual result of his efforts, and on one occasion he only made four shillings. Sometimes, however, “Tickets” himself takes the brush in hand, and, as it will be seen, even ventures to copy from nature.

Under such circumstances economy is not only a virtue, but a necessity; and, but for the frugality and sobriety which generally distinguish a Frenchman, “Tickets,” as he is familiarly called by the poor among whom he lives, would have come to grief long ago. Indeed, I could not help noticing that he was treated with a certain amount of respect by his neighbours, and I was not surprised to hear that his story elicited the sympathy of a philanthropist whose name should be familiar to the reader. Mr.George Moore happened to call last Christmas at the model lodging-house where “Tickets” and his associate used to live. He was so interested in their little industry that he determined to give them a better start. The painter had considerable difficulty in accomplishing his somewhat delicate task in the crowded kitchen and common room of the lodging-house; Mr. Moore consequently furnished a private room for him, and paid a month’s rent in advance. On the other hand, to facilitate “Tickets” in his efforts to obtain orders, he bought him about thirty shillings’ worth of clothes; and since then the associates have been able to work their business with more success.

The bad weather has, however, been a great bar to their prosperity. Cards are only required in fine weather, when pedestrians loiter about, and there is a better chance of tempting them by startling announcements affixed to the goods in shop windows. Nevertheless the hero of this chapter is still buoyed by sanguine expectations. He hopes that the number of his customers will gradually increase, and that he will be able to save on his earnings. Then, like a true Frenchman, he will return to France, and purchase the goodwill of some small shop. In the meanwhile he observes the strictest economy. He never drinks. His bed costs him two shillings a week. His breakfast consists of cocoa and bread and butter, the former being more nutritious than tea. For dinner he generally consumes a pennyworth of potatoes, with a herring or a haddock and a cup of tea, while his supper consists of bread and cheese to the value of twopence. It is only on days of exceptional good fortune that he indulges in a little meat. For a man of comparatively speaking good education this is but sorry fare; and I could not help thinking, while listening, as one by one “Tickets” related the various incidents of his career, that his first employer, the linen-draper of the Rue de la Chaussee d’Antin, had perhaps lost a good servant. If this Parisian tradesman could have displayed a little more kindness and consideration, his assistant would not have been tempted to embark on a life of adventure ending in shipwreck amid the slums of London.

A.S.