FORMERLY the 5th of November was simply a day of national rejoicing, principally celebrated by boys. The poor have, however, contrived to turn this anniversary to some account, and many bad debts, arrears in rent, huckster’s bills, &c., have been finally settled with the profits derived from exhibiting Guy Fawkes. About thirty or forty years ago only boys carried guys about. These were of a diminutive size, and uniformly represented Guy Fawkes. The sole object of the boys who made these demonstrations was that of enjoyment and they only looked forward to a bonfire, and a brilliant display of fire- works in the evening. Now, however, the parading of a Guy Fawkes may be considered in the light of a commercial undertaking, and the organizer of the show may undoubtedly be ranked among the street impresarii who prepare open-air entertainments. This comparatively novel state of affairs originated at the time of the “No Popery” agitation that ensued after the division of England into papal bishoprics. Lay figures representing Cardinal Wiseman, the Pope, and Guy Fawkes fraternizing together over a powder barrel, were dragged about the streets and greeted with cries of “No Popery,” followed by showers of pence. Costermongers, and other persons who earn their living in the streets, did not fail to profit by such opportunities. They saved money for weeks previously, and expended considerable sums in dressing and preparing gigantic guys, it having been ascertained by experience, that the more elaborate the show, the greater the receipts. Gradually, however, the excitement with regard to the spread of Roman Catholicism in England subsided, and at the same time, the number of Irish poor who live in our large towns greatly increased. These latter did not fail at times to express their resentment against the Guy Fawkes demonstration. Fights often ensued, and the Irish frequently succeeded in tearing expensive guys to pieces, thus wrecking the show, and destroying all hope of gain. Evidently, this form of speculative enterprise was losing ground, and would have died out altogether but for the modifications introduced.

It was discovered that lay figures, representing unpopular persons other than Guy Fawkes, proved equally amusing to the public, and were not so likely to be attacked by the Irish. Thus, during the Crimean War, effigies of the Emperor Nicholas were far more applauded than the stale representation of the Gunpowder Plot. Nor have the figures always been of political significance. Of late years, Madame Rachel and Mrs. Prodgers were burnt in effigy amidst cries of undivided enthusiasm. The Irish, as well as the general public, enjoyed the skit at Mrs. Prodgers, particularly as there are several Hibernian cab-drivers, and this is an important consideration. In the wealthy quarters, but little interest is manifested in these tawdry and clumsily-built figures. The rowdies and rough horse-play that follows a guy is naturally distasteful to the West End, and greater receipts, therefore, are made in the poorer quarters, and here the Irish abound.

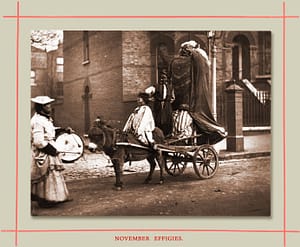

The preparation of a Guy Fawkes, or his modern substitute, whatever that may be, is a matter of considerable difficulty to the persons who undertake such ventures, for they are generally very restricted in their means. Spangles and paper play a prominent part in the apparel of a guy. But now it is also the fashion to dress the men and boys who attend, and sometimes clowns are engaged to follow and amuse all who deign to look at the show. The accompanying photograph is that of a nondescript guy, somewhat clumsily built up by a costermonger who lives in the south-east of London. This meaningless monstrosity, together with the absurd appearance of the man in woman’s clothes, amuses some persons, and the conductor of such an exhibition can hope to realize about thirty shillings the first day, a pound on the 6th of November, and ten or fifteen shillings on the 7th. With this money the cost of getting up the guy must be refunded, and a shilling or eighteenpence per day given to the boys who help to swell the cortege. The boys’ share of the proceeds is consequently somewhat out of proportion with the time and cheers they devote to promoting the success of the enterprise; but it is argued that they enjoy the fun, while to their seniors the venture is attended with some risk, and is only considered as another form of labour for daily bread. Hence the absence of the joviality and real lightness of feeling which characterize the masquerades of the continent, where pleasure is the sole object in view. It has often been remarked by foreign critics, that Englishmen do not know how to enjoy themselves, and certainly nothing can be more melancholy than some of these Guy Fawkes exhibitions. In spite of assumed gaiety and continual cheering, the men who lead the guys about have often care-worn faces, which betoken an anxious and hard struggle for bread, and show that they have not in the least degree abandoned themselves to the pleasures of a holiday, but have on the contrary converted what might be a holiday into a period of special exertion, speculation, anxiety, and fatigue.

Sometimes, it is true, when the labour is all over, and the money has been shared, there is some feeble attempt at rejoicing. But even then the guy must not be burnt its clothes are too precious, the spangles might be used again next year.; At most the straw, saw-dust, and wood shavings are extracted, and a bonfire lighted with these combustibles. Finally, what might have been an English carnival degenerates into a bout of unwholesome drinking in low public-houses. Here the Guy Fawkes men, like the English poor generally, show how devoid they are of ingenuity when there is a question of amusing themselves, and spend their hard-earned money in a form of drink which only increases their natural dulness. How different are the great historical processions which enliven the streets of the antiquated towns of Belgium, recalling the great struggles for religion and political liberty, inspiring every spectator with a due sense of reverence and gratitude for the deeds accomplished by their ancestors, diffusing some knowledge of history, and spreading the taste for what is truly artistic and picturesque! How different also in its liveliness, and in its real and for the most part innocent enjoyment, is the carnival at Rome! But we in England must apparently rest content with barbaric and uncouth exhibitions, some not even as good as that which is before the reader. In these hideous guys, we find evidence to corroborate the lack of artistic sense which is one of the greatest failings of the English race. At the same time, they occasionally testify to a certain rough sense of humour, and further serve as a public pillory, enabling the people to vent their anger on the effigy of some unpopular character.

A. S.