THE street purveyors of shell-fish find their principal customers among the poor in such quarters as Whitechapel, Drury Lane, the New Cut, Lambeth and in the immediate neighbourhood of theatres and places; of amusement. One of the chief elements of success in this, as in other branches of street industry, lies in selecting a suitable “pitch for the stall. In answer to my inquiries on this subject, an old hand in the trade said, “If a friend should ask my advice about starting, I should say, Cruise round the likeliest neighbourhoods, and find out a prime thirsty spot, which you’ll know by the number of public-’ouses it supports. Oysters, whelks, and liquor go together inwariable; consequence where there’s fewest stalls and most publics is the choicest spot for a pitch. See you choose the right side of the street. There’s al’ays two sides of a street if it’s any good, one’s the right side for custom. Don’t know ’ow it comes, whether it’s the sunny side or what, but it’s so, and it’s so much so that it makes all the differ in trade. Your pitch should be close again some cab-stand or omnibus-yard, or about a market-place. Cabmen and men on the road are uncommon partial to our goods. Next to getting a proper pitch is making the barrow look as tempting as the “fish is good. But a man should serve a sort of apprenticeship before he can hope to please the public with his barrow and his cooking. It’s not enough to be able to tell a hoyster from a whelk, it’s to know a good un when he sees it, and tell its wally in the market. Hoysters wants no cooking, but whelks, eels, and herrings should be kep’ in stock cooked to a turn.”

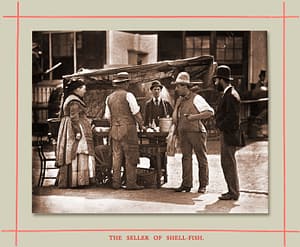

Although my informant was of opinion that a professional reputation could only be achieved by a course of regular training, there are many well-known whelk and oyster men in London who have served no apprenticeship to the trade. The owner of the barrow photographed is one of this class of untutored whelk men, who recounted his experience of street life in the following words : “Whelk selling is not my choice as a trade, I’d cut it to-morrow if I could do anything better. It don’t pay more than a poor living, although me and my missus are at this here corner with the barrow in all weathers, ’specially the missus, as I takes odd jobs beating carpets, cleaning windows, and working round the public-’ouses with my goods. So the old gal has the most of the weather to herself. I have to start every morning about five for Billingsgate, to lay in stock for the day. I require about ten shillings in money with me. When they’re in I usually get about a hundred oysters. This morning I had only twenty-five. Sometimes they are six shillings a hundred half-a-crown. I sometimes can work off a measure a day, on Saturday. The oysters on the barrow, with pepper, salt, and vinegar, fetch from a penny to three halfpence : I tries it on twopence for big uns. The whelks are not so easily managed. They must be bought alive, and boiled alive, till they comes out of the shell, and then served up with vinegar-sauce, same as oysters. I laid in twenty fine herrings this morning. There they are, cooked, or soused, as they call it, same as usual. They fetch a penny and three halfpence apiece. The whelks come into Billingsgate very irregular. Some mornings there will be about a couple hundred sacks, other mornings there’s none to be bought for money. This makes our business uncertain and unprofitable, as they vary in price, and we always have to sell ’em about the same figure that is, ; five or six a penny small, with sauce four a penny large. I’ve been told they are; difficult to catch. They are nice about their bait, and prefer it salted to fresh. Perhaps they might like fish sauce with it’; can’t say. Crabs and lobsters is what they likes best, and you’d hardly believe they can suck a lobster clean out of its shell, leaving it whole in every claw and joint. When whelks can’t be got, I take more oysters and some Dutch eels. The regular shop men come first to the market. It’s after they are done buying we gets what’s left at a cheaper rate. The eels and other fish we gets ain’t perhaps the best, but they’re tidy goods for all that. Hot eel selling it’s only took up by turns by whelk sellers. The eels wants good cooking and making into a kind of soup that goes down well with our class of customers in cold weather. The fish must be cut up, cleaned, and dressed, and after that’s done boiled in flour and water. The soup has then to be made tasty with spices, parsley, vinegar, and pepper. You see that youngster coming with his news- papers. He’s one of my best eel customers. He and another works the corner where the ’busses stop with ‘Echos.’ Whenever a gentleman gives him a penny, and takes no change, he comes here fora halfpenny-worth of eels.” The little news-vendor came briskly forward, eager for his favourite delicacy. “Spoon ’em up big, gov’nor,” he said; “this is the third go this arternoon!” He had sold four shillings’ worth of newspapers, and earned a profit of eightpence on his afternoon’s work. This sum was sacredly set aside for his widowed mother, while the extra halfpennies he might chance to get from good-hearted customers were spent in food for himself.

After this characteristic episode the whelk man proceeded with the following biographical sketch :- “That boy has a hard life, sir, out in all weathers, but so is the lot of most on us in the street. It’s perhaps harder to the likes of me, as I was not used to this sort of business. Tot many years ago me and my missus had a green-grocery shop. It was a good going concern, and might have made money for us. But one year, when small-pox was bad, my two boys and the other children was all took with it. The hospital was full, and anyhow we thought we could pay doctoring, and nurse ’em at home. It was a mistake for ’em and for us. The two boys, as fine fellows as ever stepped on English ground, died. we had had two months of it then, and all that time, and for a while after, never saw nobody save the doctor. Our customers every one left. The whole trouble was so hard on me that my boys had to be buried at the expense of the parish. More than that, I had to sell my horse and cart. and everything we could well spar to get food. I tried on business again, when the beds and house had been cleaned; but it was no go, nobody would buy any more, as if every blessed cabbage had carried plague in its blades. Some of my friends, ‘bus-men, seeing my plight, advised me to go fish selling, and made me a gift of a basket. That was the first of my street life. These men bought all they could from me, and I worked round the public-houses with the rest. By degrees I made my way until the master of the “Greyhound,” over there, gave me leave to pitch my barrow opposite his door, where it have been ever since. The barrow was part of my old stock, rigged with a canvas cover, to keep the sun from spoiling the goods. I lose a good deal by spoiling, sometimes as much as a shilling a day. When the things won’t sell, and we can’t eat ’em all at home, they won’t keep fresh till morning. At least the profit from the barrow is never over five shillings a day, often not so much. I have always, from pride partly, kep’ a good home over our heads. We live in a sort of mews, and pay seven shillings a week rent for four small rooms and kitchen. The owner has stuck to us all through, although, at times, we have not been able to raise the rent. He has took it out in carpet-beating, and odd shillings as we could pay ’em. We have to be out all day, and leave the children at home. Me and missus runs down now and again to have a look at ’em. The oldest is in service, and the others mind one another. Three of ’em goes to school. At night one of us sees them abed, as it’s late, sometimes half past twelve, before we gets home ourselves. I have still some debts to payoff, and I’ve the heart to live square and pay all I owe. But it’s hard to pick up money on the streets; there is so many at the same game now, that it’s about all we can do to get food. Fridays and Saturdays we stands a better chance of extra custom. Fish on Fridays goes down with the Irish, and on Saturday nights we get often a better class of customers than on other days. The workmen and their wives and sweethearts are about then, and hardly know how to spend their money fast enough. After visiting the public-houses they finish up with a fish supper of the very finest sort. Although I say it, no finer can be got, not at Greenwich or anywhere else. I’ve got to know exactly what I am about, and always to keep things going on the barrow in a style that brings folks back again. It’s no use for a man always on the same pitch going in for the cheap and nasty; he couldn’t stand a day against the competition of his neighbours. I never pick out anything that looks the least thing gone, for fear of losing the run of trade. When it’s possible to work off some doubtful goods is at night, at the bar of a public-house, when the men drinking are too far gone to be nice about smell or taste, so long as they gets something strong. But even that is a dangerous game to be tried on too often, so I for my part leaves it alone.”

A. S.