THE sufferings of the poor in Lambeth, and in other quarters of the Metropolis, caused by the annual tidal overflow of the Thames, have been so graphically described as thoroughly to arouse public sympathy. The prompt efforts of the clergy and the relief committees in distributing the funds and supplies placed at their disposal, have done much to allay the misery of the flooded-out districts. Feelings of apprehension and dread again and again rose with the tides, and subsided with the muddy waters as they found their way back into the old channel or sank through the soil. The public have settled down with a sense of relief, and the suffering people returned to rekindle their extinguished fires and clear away the mud and debris from their houses; to reconstruct their wrecked furniture, dry their clothes and bedding, and live on as best they may under this new phase of nineteenth century civilization.

Meanwhile the Metropolitan authorities, lulled to a sense of temporary security, have adopted no satisfactory measures to prevent the recurrence of similar disasters. A dangerous experiment is being tried with the health of the community at a time when epidemic disease is only held in check by the most vigilent efforts of modern science. It would be difficult to conceive conditions more favourable to the growth of disease than those at present existing in the low-lying, densely populous quarters of Lambeth, that have been invaded by the floods.

In China, the people get used to floods, simply because they know that river embankments are costly, and not likely to be erected. The Chinese, some of them, construct their houses to meet emergencies. I have heard a Chinaman boast that a mud cabin was the fittest abode for man. In case of flood it settles down over the furniture, keeps it together, and forms a mound upon which the family may sit and fish until the flood abates. When the waters have subsided, the owner, with his own hands, erects his house anew, and calmly awaits the advent of another flood. In Lambeth the conditions—at present at least—are altogether different. There are no mud huts and no wholesome fish in the waters of the Thames. Nor when the waters recede are the conditions so favourable to the maintenance of health. The high tides have left a trail of misery behind, and in thousands of low-lying tenements, a damp, noxious, fever-breeding atmosphere.

A few hours spent among the sufferers in the most exposed neighbourhoods will convince anyone that the danger is not yet over; that disease may still play sad havoc among the people. The effects of disasters are still pressing heavily upon a hard working, under-fed section of the community. Rheumatism, bronchitis, conjestion of the lungs, and fever have paralyzed the energy of many of the bread-winners of the families of the poor. I, myself, have listened to tales of bitter distress from the lips of men and women who shrink from receiving charity.

The localities in Lambeth most affected were Nine Elms, Southampton Street, East and West, Wandsworth Road, Hamilton Street, Portland Street, Fountain Street, Conro Street, Belmore Street, High Street, Vauxhall; Broad Street, William Street, Belvidere Road, Belvidere Crescent, Vine Street, Bond Street, Duke Street, Prince’s Street, Broadwall Street, Stamford Street, Prince’s Square, and Nine Elms Lane.

Although the distress was not confined to any particular class, the majority of the sufferers are poor, and their misery was greatly intensified by the loss of furniture and bedding. Heavy losses were also incurred by the higher classes of working men; such, for example, as had invested their savings to purchase their houses through Building Societies. The structural damage done had to be repaired, thus throwing an additional burden of debt upon the prospective owners of small properties.

In such neighbourhoods as Broadwall Street, houses containing four apartments are let at weekly rentals varying from seven shillings and sixpence to ten shillings. These houses are, many of them, let to the men employed in neighbouring works, and to labourers engaged about the wharves and warehouses on the south of the Thames. They are again sublet, so that two or three families frequently shelter under one roof. Each family occupies one or two rooms at a weekly rental ranging from half-a-crown to five shillings.

In one room I found a young married couple and their baby tended by an aged female relative. The husband is a labourer, but the floods had thrown him out of work, and, do what he would, he could only manage to earn about two days’ wages during the week. The mother-in-law, a sempstress, had contributed to their support, the rent had fallen into arrear, but the landlady had kindly agreed to receive it in instalments of a shilling, or two shillings, at a time until the husband had secured permanent employment. I was much struck with the bright, cheerful appearance of the comely young wife, and the success of her efforts to maintain a clean, comfortable, and attractive home to cheer her husband on his return after his wanderings in search of work. “If my lad,” she said, “could only get something to do, steady-like, we would be happy enough, but this want of work is hard on us, and like to break down a good man!”

In woeful contrast to this interior was another, a few paces further on, occupied by a widow, her son, and daughter. In no land, savage or civilized, have I seen a human ,abode less attractive and more filthy. The mother, who goes out” charing,” had seemingly neither the time nor the opportunity to render her apartment habitable. It was at her own invitation I followed her, as she said she had something to say to me. At a loss to conjecture what her communication might be, I made my way along a dark passage to a small doorway, and stepping over an accumulation of turnip-tops and mingled garbage, entered a room measuring about eight feet by ten feet. The walls were begrimed by smoke, and such portions of the floor as were seen were black and damp. The tidal overflow had registered its rise by partially cleansing the walls to a height of four feet, and by leaving the paper hanging in mouldy bags around. In one corner stood the remains of six sacks of coal and coke, ” the gift of the good gentleman.” On a dark unwholesome bed lay a heap of ragged coverings, bestrewn with some articles of tawdry finery, and on one corner sat a little girl, whose bright dark eyes shone through a mass of matted hair. A broken chair was propped against the wall, near a chest of drawers warped and wasted by the water. The fire burned with a depressing glimmer, as fitful gusts of foul air found their way through a heap of ashes on the hearth: over the mantelpiece hung a series of small photographs, making up the collection of family portraits of husband and children who had passed away.

“I am sick of it all,” said the woman. “I wish I were out of it, done with it, God knows! Look at me, sir. Do you see that bruise on my face? My daughter struck me down-with her fist this morning, because I would not let her se1l the clothes off my back. She wont work; she lives upon me. She had been out all night last night, and came home this morning like a mad woman, and I have driven her from my door!” She came home! I involuntarily glanced round the home of this unfortunate outcast, but saving the pictures, and the bits of cheap finery, there was nothing there to woo her back from the streets. The widow went on to say that she had some comfort in her son, who makes good wages in a mason’s yard. “I live for my boy and he lives for me, but since the floods he has been troubled by a hacking cough; I don’t like to hear it, and it don’t leave him, sir. As for myself, I have never felt right since that awful night, when with my little girl I sat above the water on my bed until the tide went down.”

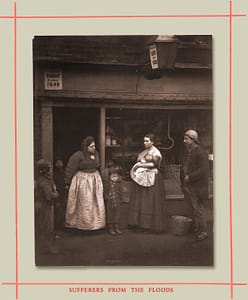

The reader will understand why I have brought him face to face with a group of the people who suffered from the Lambeth floods, in preference to photographing a street under water.

It is with the people and their surroundings that I have chosen to deal, in order to show that the floods have inflicted a permanent injury upon them, and that a succession of such disasters may at last affect the health of the metropolis at large.

The group was taken by special permission in front of the rag store of Mr. Rowlett. The Rowletts have occupied the house for twenty-seven years, but it is only in recent times that the water has invaded their premises. The family may be described as prosperous, at least they were prosperous, but the losses caused by the inundations and the failing health of Mr. Rowlett—who is now a confirmed invalid— have narrowed their means. In Mrs. Rowlett’s own words, “The water has taken us down a bit, and the last midnight flood was too much for my old man. He has now severe congestion of the lungs. Had it not been for the shop-boy, our losses would have almost been beyond repair. The boy was on the watch, and in time to enable us to save a few things: he appeared below the window, shouting, ‘The tide! the tide!’ We knew what that meant and saved all we could. Our heaviest loss was made four years ago. It was so heavy we had to part with our horse and van to keep things going. Our goods, rags, and waste-paper were soaked, and we sold tons for manure. We have never been able to recover our losses. Since the embankment was built, part of our business has gone down the water with the wharves. The beach pickers don’t pick up so much old iron and things now. At first I was too proud to take help, but now I am fain to get a little assistance when I can. As they say, the water might be stopped if the Government would only do it. You see the water don’t come into the drawing-rooms of fine folks. We would hear more of it if it did. It’s never been into the Parliament Houses yet, sir, has it ?” I assured the good woman that it had not, but that the question of the floods would be in the House before long, and that something would probably be done.

“We saved our piano you see,” continued Mrs. Rowlett, “it’s what I prize most, next to my daughter who plays it. I had her taught by times, as I could spare the money. We have nothing to leave our children, but they got a good education, so my girl if she needs to work can teach music. I bought the piano as poor folks buy most things, by paying a few shillings or a few pence at a time to dealers who supply every thing.” Our conversation was interrupted by the entrance of a pretty, poorly-clad little girl, who said, “Mrs. Rowlett, mother sent me to pay.the twopence for the boots, and I was to ask if you had another tidy pair of stockings for Nell.” “No, darling, I have not, but I will keep a look out for a pair.” Mrs. Rowlett explained that the girl was one of a large family, and that the twopence was payment ‘for a pair of boots and a pair of stockings she had picked out of a heap of rags and paper.

The woman in the centre of the group with the child in her arms, occupies with her husband and children an adjoining house. They are country folks tempted into the town by the hope of higher wages. The husband is a horse-keeper, whose working hours are from four o’clock in the morning to eight o’clock at night, and on Sundays from six in the morning to six at night, with two or three hours intermission when the horses do not want tending. His wages are twenty-five shillings weekly. Part of their house is sublet to another family. The woman is a skilled lace-maker. She used to work at home with her pillow, pins, and bobbins, but being unable to find a market in the neighbourhood for her fine wares, she has discontinued working. She made very beautiful black silk broad lace at two shillings or half-a-crown a yard. In spite of foul exhalations, mouldy corners, and water-stained walls, the house in which these people lived was clean, comfortable, and attractive. But the family had not escaped colds and rheumatism. The woman complained of a constant cough, and severe pains in her chest and between the shoulders; while one of the children looked sickly and as if it would hardly survive to witness the probable floods of 1878.

On the right of the photograph is a character of an interesting type. A sort of odd-handy man. Jack Smith is well known in the neighbourhood as a local comedian, whose tricks, contortions, and grimaces are the delight of many a pot-house audience. ” Yes,” said an admirer of Jack, ” he’s a rum’un, he is; he can do the ‘ born cripple,’ or the man starved to death, or anything a’most, and the jury inquestin’ his remains.” During his working hours Jack Smith is called a “beach-picker,” or “tide-waiter,” or a mud-lark. His business takes him wading over the shallows of the Thames, where he picks up fragments of iron, coal, wood, and waste materials. For such miscellaneous wares he receives one shilling or two shillings per cwt. As I have already pointed out, this class of river industry has been partially paralyzed by the erection of the embankment and the removal of the old wharves.

During the recent overflows this “odd man” found many new and comparatively lucrative fields of labour. The water in Prince’s Square, after submerging the ground floors of the houses, rose to a height of four feet in the rooms above. A ll this took place in defiance of the Herculean efforts of a band of men of Jack Smith’s class, who were engaged to stop windows and doors with mud, clay, and pulp formed by the paper floated out of extensive printing-works in the neighbourhood. Some of the barricades resisted the pressure of the water, but many more gave way, and the tide rushed in with such force as to break down partition-walls, shatter furniture, and send iron boilers adrift from their brick-work. The “odd man’s” hands were full, at one time carrying women and children to places of safety, at another baling out an area with his bucket, or cleansing an interior.

J. T.