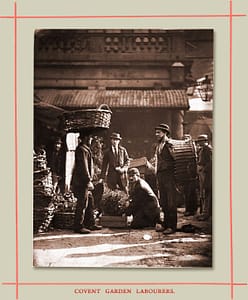

THE number of persons who obtain out-door or street work at Covent Garden Market is so considerable that it is necessary to devote more than one chapter to the subject. Some account has already been given of the flower-women who frequent the market; and the accompanying photograph represents a group of labourers who are in the service of Mr. Dickson, the well-known florist. Their business is strictly limited to flowers, and they never touch either vegetables or fruits. Nevertheless I am informed that there are five hundred flower stalls at the wholesale flower market, and, at a rough computation, two thousand men are engaged to bring and grow stock for these stalls; while another two thousand men find employment in distributing the flowers to their various purchasers. Only a small proportion of these latter are seen at Covent Garden during the daytime; it is in the early morning that they congregate on this spot, and they are soon scattered again to all parts of the metropolis, laden with plants of every description. The labourers employed by the tradesmen who have shops or stalls at Covent Garden are divided into the job-workers and the regular hands. The former are by far the most numerous; and, but for their improvidence. might be as well-off financially as those who receive regular salaries. The odd-men, as they are sometimes called, are paid for each commission they execute, for every parcel they deliver. Indeed they are often paid twice over-once by the tradesman who has sold some Rowers, and again by the purchaser on the receipt of the same. In busy times, therefore, these men may occasionally make as much as £2 10s in a week. On the other hand, and during the dull season, they often pass entire days without earning anything at all, and at best scarcely obtain enough to procure the barest necessaries of life. If, however, they were able to strike an average in their earnings, never spend more, and save from the prosperous season to meet the exigencies of the less busy months, they would lead a life of comparative comfort. But such prudence would be altogether foreign to their natures. Resisting the temptation of spending the money actually in hand would be considered a far greater hardship than the privation to be subsequently endured. The greater number of these men are bred and born in the immediate neighbourhood, and not a few are qualified under the generic term of Seven Dials Irish. On the whole, however, they are a reliable body: they are addicted to drink, and occasionally present themselves at the house of a customer in a very disgraceful condition; but disasters of this description happen more or less in all trades where a number of unskilled labourers are engaged to fetch and carry. A t th e same time, any g ross misconduct is not tolerated. The men have to obtain a ticket from the superintendent of the estate, for which they pay eighteen pence. This gives them the privilege to ply for work at the market; but this licence is withdrawn when complaints are made against the bearer.

From this large class of chance labourers a few are selected, for their steadiness, or energy and willingness, and offered regular employment. A position thus acquired is at once more respectable and certain; the men have the disadvantage of working very hard during the busy season for the same rate of wages; but, on the other hand, they are equally well paid when there is nothing to do. Early in the morning, before five o’clock, the men have to be in readiness to carry from the wholesale market the stock bought for the day’s business. This has to be arranged all round the shop, with a view to effect; and, as the day approaches, ladies and gentlemen come from all parts of the metropolis to give orders or to select flowers. Hampers are filled and rapidly carried off to the houses of the various purchasers. Then there are ball- rooms or dinner-tables to be decorated. Steady, trustworthy, and experienced.men must be engaged for such work. They must also possess some taste, and a certain artistic sense of the fitness of things, or they would be unable to group the flowers in a harmonious manner. It is not surprising, therefore, that men gifted with these qualities should often earn thirty to thirty-five shillings a week. Their wages, it is true, rarely amount to more than £1 per week; the rest is derived from customers who consider themselves bound to give small gratuities.

There are also a few men who through ill-health or lack of muscular strength cannot carry heavy pots of flowers, and these are employed in the bouquet department. They help to gum the flowers, to sort and cut them. It will have been noticed how firmly the leaves of a flower adhere to the stem, though it may be in full bloom and subjected to an unnatural ordeal of travelling and shaking. This result is obtained by dropping a little gum into the centre of the flower. It is quite imperceptible when dry, but it causes the leaves to adhere so firmly that death itself often fails to make them drop off. I had a long conversation with one of the men who devotes the greater part of his time to this work. He is located in a cellar underneath a shop in the central avenue; and justly complains that his employment is most unhealthy. The scent escaping from the mounds of flowers that surround him in so confined a space is very deleterious, and induces chronic headache and much uneasiness. But for an occasional change of air asphyxia would result. Then again his eyesight is seriously affected. If, for instance, he is busy during a whole day gumming nothing but geraniums, the constant and unrelieved glare of the red overbalances and disturbs the power of vision.

In the arranging of flowers for bouquets or button-holes women are preferred. They display more taste, and the button-hole flowers are so gracefully combined, and so rare and exquisite, that they are generally sold for a shilling or eighteen pence- a rather extravagant charge for an ornament that can only last a few hours. It has become the custom to place them in glasses by the plate of each guest at dinner parties; so that, though about the same number of “button-holes” are sold, they are for the most part bought by the hostess, and not, as formerly, by the gentlemen guests. There is also a fashion in the colour of flowers, for they are selected to match the style of dress in vogue. Thus for the present year pink-and-white and yellow-and- white flowers are at a premium, and de rigueur in fashionable circles. But as the Court is condemned to mourning, white flowers must for the moment assume the ascendency, to be relieved with the violets in autumn should the mourning continue.

During the winter a second or Christmas season revives the trade in Covent Garden and then the flowers sold are for the most part imported, a great many coming from Nice. In the summer season, the English flowers, reared at a distance of about twenty miles from London, have almost undivided sway over the popular taste. To the labourers, however, the origin of the plants is of little consequence so long as the pots do not weigh too heavy, or if liberal “tips” are forthcoming to reward them for carrying these attractIve burdens.

A.S.