In Drury Lane there is a house which has been celebrated for more than a century. It was a “cook-shop” in Jack Sheppard’s time. This notorious criminal often dined there, and it is now still frequented by hungry convicts or ticket-of-leave men, who, find kindly welcome and may, if they choose, receive wholesome advice from the owner of this strange establishment, whom I now propose to introduce to the reader. Mr. Baylis, by no fault of his own, as he himself justly urges, was born under most unfortunate circumstances; though in legal parlance a filius nullius, he was in reality the son of a highly-respectable and wealthy magistrate of Oxford. His mother had been a maid-servant in this gentleman’s house; and, as the position of the latter improved, he imagined it indispensable to rid himself at once of both mother and son. The former he contrived to marry to some ruffian well known in the slums of Westminster, and who was probably glad to accept the bribe which I presume must have been offered him. As for the boy, he had been for some time at a school at Chipping Norton; his marvellous likeness to his father occasioned, however, so much gossip that he was finally despatched to London, to fight his own way in life, though but nine years old. This occurred in 1839, so that the journey was performed in a coach, and Baylis was met on his arrival by his mother and a strange man whom he was told to call father! The poor boy, however, though scarcely able to understand his position, nevertheless refused to confer on the stranger a name implying a sacred tie he knew did not exist between them. At the very onset he conceived a deep dislike to the man, and subsequent experience proved that he had judged him correctly. His mother’s husband was one of those low bullies who are familiar with every vice. He lived in Westminster, and behaved in so brutal a manner, constantly beating his wife, always quarrelling, and often drunk, that the poor boy scarcely dare show himself in this wretched home. The life of a street Arab was a preferable alternative, and Baylis therefore left his mother’s lodgings to pick up his fortune in the gutter. He slept anywhere, that is to say, on doorsteps, under bridges, or at times he would have the good fortune to creep unperceived into a cart or cab left in a wheelwright’s yard to be repaired. As for money, he occasionally received a few pence for holding horses, or at times he was engaged to blow the bellows at a smithy. The first regular work was obtained in 1840, when he was engaged as errand boy by a doctor, who gave him the munificent salary of eighteen pence per week, but ultimately discharged him for playing at marbles!

During several years Baylis continued leading the life of an Arab, living in a semi-wild state, fighting innumerable battles, enduring the tortures inflicted by the bullies who abound in the streets; often starving, generally underfed, and always in rags. At last, inspired with lofty ambition, the poor boy migrated from Westminster, thinking he would find more gentle treatment and better fortune the other side of the Park. Nor was he disappointed in his anticipations. He made friends in the parish of St. James, and was given something like regular employment at a blacksmith’s forge in Ham Yard. This, however, did not last for long, and young Baylis had to resort to many expedients to keep body and soul together. Nevertheless, during all these trials and struggles, he always proved himself willing to work and thoroughly trustworthy. These qualities attracted the notice of some neighbours, and he was sometimes given work which testified to the confidence of his employers. He was admitted into some good houses; and it was while engaged cleaning the windows of a fashionable apartment in Jermyn Street, that fortune suddenly smiled upon him through a pane of glass. The door of the back room had unexpectedly opened, and a swarthy gentleman made his appearance in a long robe slashed with gold braiding and a smoking-cap resplendent under the glitter of a gold tassel. Alarmed at the splendid presence of this gentleman, the street Arab hastily snatched up his basin of water, his rags and leather, and attempted to leave the room. But the gentleman in gold called him back, and after ascertaining that Baylis lived alone, had practically speaking no parents, but bore a good character in the neighbourhood, he engaged him as his valet. The boy pathetically pointed to his ragged clothes, and suggested that he was totally inexperienced in the duties of a valet; but these objections only increased the gentleman’s desire to secure his service. He gave him several suits of clothes and promised, what seemed fabulous wealth to the poor boy, namely a salary of £1 per week. To the street Arab this sounded as if the gates of El-dorada had been thrown open. He had no fault to find with his new master. He was a foreigner, but evidently extremely wealthy, for he sent Baylis to cash a cheque for £200 every week. Further, he was constantly at the Russian embassy, and once a week Baylis took a letter to be registered at the Post Office, addressed by his master to his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias! Evidently this distinguished foreigner was a secret emissary of the Russian Government, and he thought it safer to engage a street boy as his valet than some gossiping consequential London flunky, who would have known the servants of many leading families, and spread through them many dangerous rumours concerning the mysterious avocations of his master.

For some years Baylis enjoyed an easy and almost luxurious life. He was even able to save some money, but his master was ultimately called to the continent, and after travelling with him some distance, he received his discharge when at Dresden, together with a handsome present. The Russian gentleman had been compelled to return to his own country, and for some inscrutable reason could not take his servant with him. On returning to London, Baylis sought for another similar situation, but he had only a written reference to show, his former master was too far away to confirm the good character he had given his valet. Gradually, Baylis spent all the money he had saved in advertising and waiting for employment, so that at last he was glad to accept very inferior work at a ginger beer manufacturer’s, and was subsequently in the employ of a well-known West End grocer. After some three years spent in these somewhat monotonous and scarcely remunerative occupations, Baylis contrived to learn the art of taking photographs; and entering into association with a more experienced friend, they took to the road armed with their camera. Their first stage was at a public-house at Uxbridge, and, as photography was quite a novelty in those days, a great number of persons came to have their portraits taken, and at the same time, did not fail to partake of whatever refreshments could be obtained at the bar. Thus the itinerant photographers found ready allies at the public-houses they passed on the road; and still further to cement the bond, Baylis finally married the daughter of one of these friendly publicans.

With the advent of the dark months, however, photography became more difficult, and Baylis and his bride came to spend the winter in London. As, however, something had to be done for a living, he joined the police force for four months; but, when summer came round, a child was born, and under these circumstances Baylis was obliged to abandon his hope of resuming the roving life of a photographer. Instead of four months, he remained seven years in the police, and finally only left the service in consequence of ill-health. His experiences as a policeman would in themselves form an interesting chapter. He was one out of a dozen selected to suppress the garrotting so extensively practised some years ago. Dressed in plain clothes, he was commissioned to watch for these footpads, and had the satisfaction of catching one in the very act of garrotting a gentleman. He was also appointed to a beat comprising the Adelphi Arches at the time when public opinion was so strongly moved concerning the scenes enacted under the dark shades of these lugubrious passages. This brought him into personal relation with Charles Dickens and Mr. G. A. Sala, with whom he had many pleasant conversations while guiding them through the intricacies of the Adelphi Arches and explaining all the mysteries of this notorious resort.

Like many other policemen, he had often been able to live rent free by occupying uninhabited houses. He was once asked to take up his quarters in the cook-shop of Drury Lane, while the house underwent some repairs; and when it was re-opened he remained there as a lodger. As time rolled on, he observed how the business was managed and, being of a mechanical turn of mind, conceived schemes for various improvements which would economize the fuel and utilize the steam used in cooking. Finally he contrived to purchase the goodwill of the house; and, since that day, has been the presiding genius at all banquets the poor here enjoy. For fourteen years he has taken delight in serving the wretched people around him but, remembering; his own past experience, his generosity is unbounded towards the pale-faced street Arabs who with hungry eyes frequently throng about his door. His thoughts are constantly occupied with the fate of these children, and he anxiously inquired whether I had any hope that legislature would or could adopt some effective means of protecting the children who had no parents and are left to learn every vice in the streets of London. In the meanwhile, they can, in any case, obtain enormous helps of pudding for a penny,and even for a halfpenny. Nothing is wasted in this establishment. All scraps are used, and those who cannot afford to pay for a fair cut from the joint can obtain, for a penny or twopence, a collection of vegetables and scraps mixed with soup or gravy, that contain a good proportion of the nutritive properties of meat.

This shop is, however, chiefly celebrated as the abode of ticket-of-leave men. Placing himself in connexion with the Royal Society for the Aid of Discharged Prisoners,these latter have been sent to lodge in Mr.Baylis’s house. On their arrival from prison he gives them a week’s lodging and board on credit, and also exerts himself to the utmost to find them employment. Possessing great experience in the treatment of criminals, he is soon able to detect those whom he may trust from those who are hopelessly lost to all sense of honour and honesty. The latter he is perforce obliged to dismiss, while the former generally obtain employment, and live to thank him for having redeemed them from the abyss into which they had fallen. Indeed there have been even marriages celebrated from this convicts’ lodging-house—an ex-convict figuring as the bridegroom, and, in one instance at least, a very respectable tradesman’s daughter as the bride. I should add, that one of the released prisoners ultimately married a widow who possessed fifteen houses ! In fact experience seems to have confirmed the great faith Mr. Baylis places in convicts who, after a certain time of probation, show themselves really disposed to earn their living honestly.

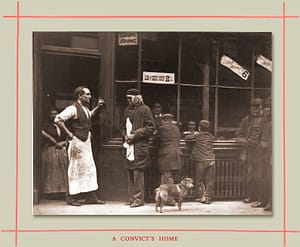

In many cases the good influences brought to bear in this house have certainly produced the very best effect ; and I have had the pleasure of sitting down to Mr. Baylis’s table with half-a-dozen of the best behaved and most inoffensive men (who were, I was informed, convicts) that I have met in the course of Street Life study. In their conversation, these men displayed an earnest determination to work, they alluded but charily to the time when they “got into trouble,” and did not resort to any hypocritical cant. Indeed, those who assume a pious tone, quote the Bible, and talk about “being saved,” and “God’s help,” and so forth, are generally the least to be trusted. It is to be regretted that the accompanying photograph does not include one of these released prisoners; but the publication of their portraits might have interfered with their chances of getting employment. Ramo Sammy, therefore, stands at the door of the convicts’ home instead. This characteristic old man, familiar to all Londoners as the tarn-tarn man, lives nearly opposite the cook-shop, and often has his meals there. But the old Indian is getting weak; he does not strike his drum with his wonted energy; and it is to be hoped that Mr. Baylis, who is officiating behind the counter, will find a titbit for him from time to time, so as to revive his ebbing vitality.

.A.S.