No doubt you have already guessed that it was the Countess Belvane who dictated the King of Euralia’s answer. Left to himself, Merriwig would have said, “Serve you jolly well right for stalking over my kingdom.” His repartee was never very subtle. Hyacinth would have said, “Of course we’re awfully sorry, but a whisker isn’t very bad, is it? and you really oughtn’t to come to breakfast without being asked.” The Chancellor would have scratched his head for a long time, and then said, “Referring to Chap VII, Para 259 of the King’s Regulations we notice . . .”

No doubt you have already guessed that it was the Countess Belvane who dictated the King of Euralia’s answer. Left to himself, Merriwig would have said, “Serve you jolly well right for stalking over my kingdom.” His repartee was never very subtle. Hyacinth would have said, “Of course we’re awfully sorry, but a whisker isn’t very bad, is it? and you really oughtn’t to come to breakfast without being asked.” The Chancellor would have scratched his head for a long time, and then said, “Referring to Chap VII, Para 259 of the King’s Regulations we notice . . .”

But Belvane had her own way of doing things; and if you suggest that she wanted to make Barodia’s declaration of war inevitable, well, the story will show whether you are right in supposing that she had her reasons. It came a little hard on the Chancellor of Barodia, but the innocent must needs suffer for the ambitions of the unprincipled—a maxim I borrow from Euralia Past and Present; Roger in his moral vein.

“Well,” said Merriwig to the Countess, “that’s done it.”

“It really is war?” asked Belvane.

“It is. Hyacinth is looking out my armour at this moment.”

“What did the King of Barodia say?”

“He didn’t say anything. He wrote ‘W A R’ in red on a dirty bit of paper, pinned it to my messenger’s ear, and sent him back again.”

“How very crude,” said the Countess.

“Oh, I thought it was—er—rather forcible,” said the King awkwardly. Secretly he had admired it a good deal and wished that he had been the one to do it.

“Of course,” said the Countess, with a charming smile, “that sort of thing depends so very much on who does it. Now from your Majesty it would have seemed—dignified.”

“He must have been very angry,” said the King, picking up first one and then another of a number of swords which lay in front of him. “I wish I had seen his face when he got my Note.”

“So do I,” sighed the Countess. She wished it much more than the King. It is the tragedy of writing a good letter that you cannot be there when it is opened: a maxim of my own, the thought never having occurred to Roger Scurvilegs, who was a dull correspondent.

The King was still taking up and putting down his swords.

“It’s very awkward,” he muttered; “I wonder if Hyacinth——” He went to the door and called “Hyacinth!”

“Coming, Father,” called back Hyacinth, from a higher floor.

The Countess rose and curtsied deeply.

“Good morning, your Royal Highness.”

“Good morning, Countess,” said Hyacinth brightly. She liked the Countess (you couldn’t help it), but rather wished she didn’t.

“Oh, Hyacinth,” said the King, “come and tell me about these swords. Which is my magic one?”

Hyacinth looked at him blankly.

“Oh, Father,” she said. “I don’t know at all. Does it matter very much?”

“My dear child, of course it matters. Supposing I am fighting the King of Barodia and I have my magic sword, then I’m bound to win. Supposing I haven’t, then I’m not bound to.”

“Supposing you both had magic swords,” said Belvane. It was the sort of thing she would say.

The King looked up slowly at her and began to revolve the idea in his mind.

“Well, really,” he said, “I hadn’t thought of that. Upon my word, I——” He turned to his daughter. “Hyacinth, what would happen if we both had magic swords?”

“I suppose you’d go on fighting for ever,” said Hyacinth.

“Or until the magic wore out of one of them,” said Belvane innocently.

“There must be something about it somewhere,” said the King, whose morning was in danger of being quite spoilt by this new suggestion; “I’d ask the Chancellor to look it up, only he’s so busy just now.”

“He’d have plenty of time while the combat was going on,” said Belvane thoughtfully. Wonderful creature! she saw already the Chancellor hurrying up to announce that the King of Euralia had won, at the very moment when he lay stretched on the ground by a mortal thrust from his adversary.

The King turned to his swords again.

“Well, anyway, I’m going to be sure of mine,” he said. “Hyacinth, haven’t you any idea which it is?” He added in rather a hurt voice, “Naturally I left the marking of my swords to you.”

His daughter examined the swords one by one.

“Here it is,” she cried. “It’s got ‘M’ on it for ‘magic.'”

“Or ‘Merriwig,'” said the Countess to her diary.

The expression of joy on the King’s face at his daughter’s discovery had just time to appear and fade away again.

“You are not being very helpful this morning, Countess,” he said severely.

Instantly the Countess was on her feet, her diary thrown to the floor—no, never thrown—laid gently on the floor, and herself, hands clasped at her breast, a figure of reproachful penitence before him.

“Oh, your Majesty, forgive me—if your Majesty had only asked me—I didn’t know your Majesty wanted me—I thought her Royal Highness—— But of course I’ll find your Majesty’s sword for you.” Did she stroke his head as she said this? I have often wondered. It would be like her impudence, and her motherliness, and her—-and, in fact, like her. Euralia Past and Present is silent upon the point. Roger Scurvilegs, who had only seen Belvane at the unimpressionable age of two, would have had it against her if he could, so perhaps there is nothing in it.

“There!” she said, and she picked out the magic sword almost at once.

“Then I’ll get back to my work,” said Hyacinth cheerfully, and left them to each other.

The King, smiling happily, girded on his sword. But a sudden doubt assailed him.

“Are you sure it’s the one?”

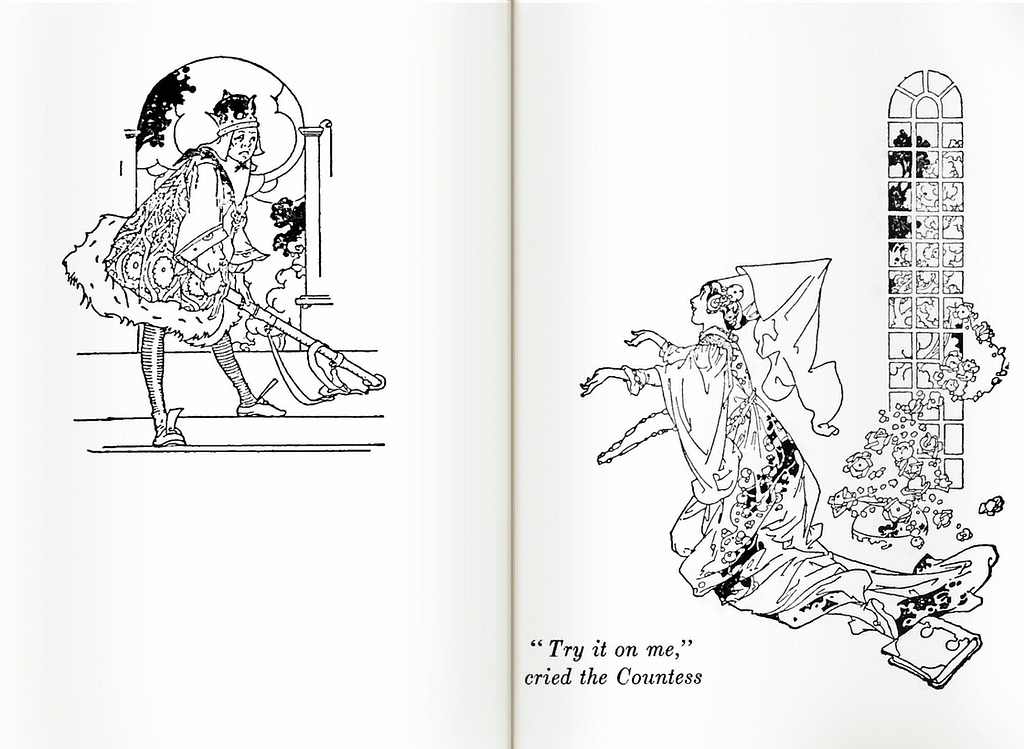

“Try it on me,” cried the Countess superbly, falling on her knees and stretching up her arms to him. The toe of her little shoe touched her diary; its presence there uplifted her. Even as she knelt she saw herself describing the scene. How do you spell “offered”? she wondered.

I think the King was already in love with her, though he found it so difficult to say the decisive words. But even so he could only have been in love a week or two; a fortnight in the last forty years; and he had worn a sword since he was twelve. In a crisis it is the old love and not the greater love which wins (Roger’s, but I think I agree with him), and instinctively the King drew his sword. If it were magic a scratch would kill. Now he would know.

Her enemies said that the Countess could not go pale; she had her faults, but this was not one of them. She whitened as she saw the King standing over her with drawn sword. A hundred thoughts chased each other through her mind. She wondered if the King would be sorry afterwards; she wondered what the minstrels would sing of her, and if her diary would ever be made public; most of all she wondered why she had been such a fool, such a melodramatic fool.

The King came to himself with a sudden start. Looking slightly ashamed he put his sword back in its scabbard, coughed once or twice to cover his confusion, and held his hand out to the Countess to assist her to rise.

“Don’t be absurd, Countess,” he said. “As if we could spare you at a time like this. Sit down and let us talk matters over seriously.”

A trifle bewildered by the emotions she had gone through, Belvane sat down, the beloved diary clasped tightly in her arms. Life seemed singularly sweet just then, the only drawback being that the minstrels would not be singing about her after all. Still, one cannot have everything.

The King walked up and down the room as he talked.

“I am going away to fight,” he said, “and I leave my dear daughter behind. In my absence, her Royal Highness will of course rule the country. I want her to feel that she can lean upon you, Countess, for advice and support. I know that I can trust you, for you have just given me a great proof of your devotion and courage.”

“Oh, your Majesty!” said Belvane deprecatingly, but feeling very glad that it hadn’t been wasted.

“Hyacinth is young and inexperienced. She needs a—a——”

“A mother’s guiding hand,” said Belvane softly.

The King started and looked away. It was really too late to propose now; he had so much to do before the morrow. Better leave it till he came back from the war.

“You will have no official position,” he went on hastily, “other than your present one of Mistress of the Robes; but your influence on her will be very great.”

The Countess had already decided on this. However there is a look of modest resignation to an unsought duty which is suited to an occasion of this kind, and the Countess had no difficulty in supplying it.

“I will do all that I can, your Majesty, to help—gladly; but will not the Chancellor——”

“The Chancellor will come with me. He is no fighter, but he is good at spells.” He looked round to make sure that they were alone, and then went on confidentially, “He tells me that he has discovered in the archives of the palace a Backward Spell of great value. Should he be able to cast this upon the enemy at the first onslaught, he thinks that our heroic army would have no difficulty in advancing.”

“But there will be other learned men,” said Belvane innocently, “so much more accustomed to affairs than us poor women, so much better able”—(“What nonsense I’m talking,” she said to herself)—”to advise her Royal Highness——”

“Men like that,” said the King, “I shall want with me also. If I am to invade Barodia properly I shall need every man in the kingdom. Euralia must be for the time a country of women only.” He turned to her with a smile and said gallantly, “That will be—er—— It is—er—not—er——. One may well—er——”

It was so obvious from his manner that something complimentary was struggling to the surface of his mind, that Belvane felt it would be kinder not to wait for it.

“Oh, your Majesty,” she said, “you flatter my poor sex.”

“Not at all,” said the King, trying to remember what he had said. He held out his hand. “Well, Countess, I have much to do.”

“I, too, your Majesty.”

She made him a deep curtsey and, clasping tightly the precious diary, withdrew.

The King, who still seemed worried about something, returned to his table and took up his pen. Here Hyacinth discovered him ten minutes later. His table was covered with scraps of paper and, her eyes lighting casually upon one of them, she read these remarkable words:

“In such a land I should be a most contented subject.”

She looked at some of the others. They were even shorter:

“That, dear Countess, would be my——”

“A country in which even a King——”

“Lucky country!”

The last was crossed out and “Bad” written against it.

“Whatever are these, Father?” said Hyacinth.

The King jumped up in great confusion.

“Nothing, dear, nothing,” he said. “I was just—er—— Of course I shall have to address my people, and I was just jotting down a few—— However, I shan’t want them now.” He swept them together, screwed them up tight, and dropped them into a basket.

And what became of them? you ask. Did they light the fires of the Palace next morning? Well, now, here’s a curious thing. In Chapter X of Euralia Past and Present I happened across these words:

“The King and all the men of the land having left to fight the wicked Barodians, Euralia was now a country of women only—a country in which even a King might be glad to be a subject.”

Now what does this mean? Is it another example of literary theft? I have already had to expose Shelley. Must I now drag into the light of day a still worse plagiarism by Roger Scurvilegs? The waste-paper baskets of the Palace were no doubt open to him as to so many historians. But should he not have made acknowledgments?

I do not wish to be hard on Roger. That I differ from him on many points of historical fact has already been made plain, and will be made still more plain as my story goes on. But I have a respect for the man; and on some matters, particularly those concerning Prince Udo of Araby’s first appearance in Euralia, I have to rely entirely upon him for my information. Moreover I have never hesitated to give him credit for such of his epigrams as I have introduced into this book, and I like to think that he would be equally punctilious to others. We know his romantic way; no doubt the thought occurred to him independently. Let us put it at that, anyhow.

Belvane, meanwhile, was getting on. The King had drawn his sword on her and she had not flinched. As a reward she was to be the power behind the throne.

“Not necessarily behind the throne,” said Belvane to herself.