King Merriwig of Euralia sat at breakfast on his castle walls. He lifted the gold cover from the gold dish in front of him, selected a trout and conveyed it carefully to his gold plate. He was a man of simple tastes, but when you have an aunt with the newly acquired gift of turning anything she touches to gold, you must let her practise sometimes. In another age it might have been fretwork.

“Ah,” said the King, “here you are, my dear.” He searched for his napkin, but the Princess had already kissed him lightly on the top of the head, and was sitting in her place opposite to him.

“Good morning, Father,” she said; “I’m a little late, aren’t I? I’ve been riding in the forest.”

“Any adventures?” asked the King casually.

“Nothing, except it’s a beautiful morning.”

“Ah, well, perhaps the country isn’t what it was. Now when I was a young man, you simply couldn’t go into the forest without an adventure of some sort. The extraordinary things one encountered! Witches, giants, dwarfs——. It was there that I first met your mother,” he added thoughtfully.

“I wish I remembered my mother,” said Hyacinth.

The King coughed and looked at her a little nervously.

“Seventeen years ago she died, Hyacinth, when you were only six months old. I have been wondering lately whether I haven’t been a little remiss in leaving you motherless so long.”

The Princess looked puzzled. “But it wasn’t your fault, dear, that mother died.”

“Oh, no, no, I’m not saying that. As you know, a dragon carried her off and—well, there it was. But supposing”—he looked at her shyly—”I had married again.”

The Princess was startled.

“Who?” she asked.

The King peered into his flagon. “Well,” he said, “there are people.”

“If it had been somebody very nice,” said the Princess wistfully, “it might have been rather lovely.”

The King gazed earnestly at the outside of his flagon.

“Why ‘might have been?'” he said.

The Princess was still puzzled. “But I’m grown up,” she said; “I don’t want a mother so much now.”

The King turned his flagon round and studied the other side of it.

“A mother’s—er—tender hand,” he said, “is—er—never——” and then the outrageous thing happened.

It was all because of a birthday present to the King of Barodia, and the present was nothing less than a pair of seven-league boots. The King being a busy man, it was a week or more before he had an opportunity of trying those boots. Meanwhile he used to talk about them at meals, and he would polish them up every night before he went to bed. When the great day came for the first trial of them to be made, he took a patronising farewell of his wife and family, ignored the many eager noses pressed against the upper windows of the Palace, and sailed off. The motion, as perhaps you know, is a little disquieting at first, but one soon gets used to it. After that it is fascinating. He had gone some two thousand miles before he realised that there might be a difficulty about finding his way back. The difficulty proved at least as great as he had anticipated. For the rest of that day he toured backwards and forwards across the country; and it was by the merest accident that a very angry King shot in through an open pantry window in the early hours of the morning. He removed his boots and went softly to bed. . . .

It was, of course, a lesson to him. He decided that in the future he must proceed by a recognised route, sailing lightly from landmark to landmark. Such a route his Geographers prepared for him—an early morning constitutional, of three hundred miles or so, to be taken ten times before breakfast. He gave himself a week in which to recover his nerve and then started out on the first of them.

Now the Kingdom of Euralia adjoined that of Barodia, but whereas Barodia was a flat country, Euralia was a land of hills. It was natural then that the Court Geographers, in search of landmarks, should have looked towards Euralia; and over Euralia accordingly, about the time when cottage and castle alike were breakfasting, the King of Barodia soared and dipped and soared and dipped again.

* * * * *

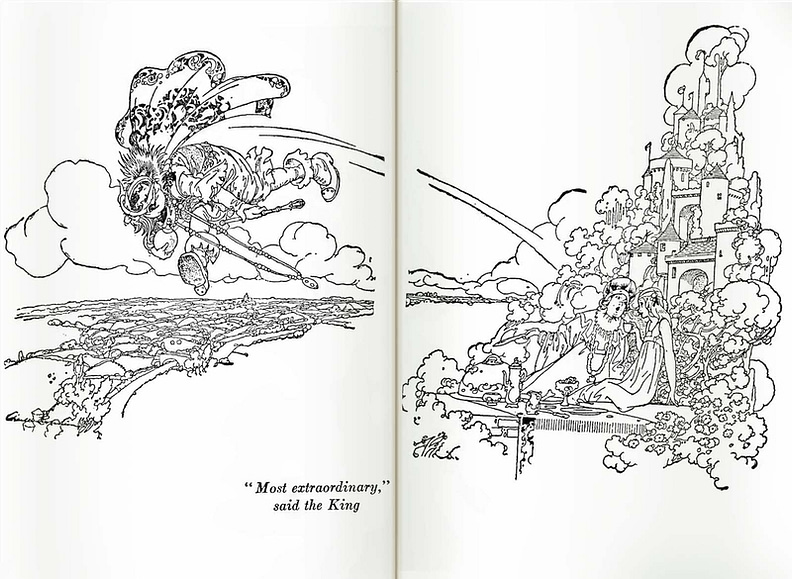

“A mother’s tender hand,” said the King of Euralia, “is—er—never—good gracious! What’s that?”

There was a sudden rush of air; something came for a moment between his Majesty and the sun; and then all was quiet again.

“What was it?” asked Hyacinth, slightly alarmed.

“Most extraordinary,” said the King. “It left in my mind an impression of ginger whiskers and large boots. Do we know anybody like that?”

“The King of Barodia,” said Hyacinth, “has red whiskers, but I don’t know about his boots.”

“But what could he have been doing up there? Unless——”

There was another rush of wind in the opposite direction; once more the sun was obscured, and this time, plain for a moment for all to see, appeared the rapidly dwindling back view of the King of Barodia on his way home to breakfast.

Merriwig rose with dignity.

“You’re quite right, Hyacinth,” he said sternly; “it was the King of Barodia.”

Hyacinth looked troubled.

“He oughtn’t to come over anybody’s breakfast table quite so quickly as that. Ought he, Father?”

“A lamentable display of manners, my dear. I shall withdraw now and compose a stiff note to him. The amenities must be observed.”

Looking as severe as a naturally jovial face would permit him, and wondering a little if he had pronounced “amenities” right, he strode to the library.

The library was his Majesty’s favourite apartment. Here in the mornings he would discuss affairs of state with his Chancellor, or receive any distinguished visitors who were to come to his kingdom in search of adventure. Here in the afternoon, with a copy of What to say to a Wizard or some such book taken at random from the shelves, he would give himself up to meditation.

And it was the distinguished visitors of the morning who gave him most to think about in the afternoon. There were at this moment no fewer than seven different Princes engaged upon seven different enterprises, to whom, in the event of a successful conclusion, he had promised the hand of Hyacinth and half his kingdom. No wonder he felt that she needed the guiding hand of a mother.

The stiff note to Barodia was not destined to be written. He was still hesitating between two different kinds of nib, when the door was flung open and the fateful name of the Countess Belvane was announced.

The Countess Belvane! What can I say which will bring home to you that wonderful, terrible, fascinating woman? Mastered as she was by overweening ambition, utterly unscrupulous in her methods of achieving her purpose, none the less her adorable humanity betrayed itself in a passion for diary-keeping and a devotion to the simpler forms of lyrical verse. That she is the villain of the piece I know well; in his Euralia Past and Present the eminent historian, Roger Scurvilegs, does not spare her; but that she had her great qualities I should be the last to deny.

She had been writing poetry that morning, and she wore green. She always wore green when the Muse was upon her: a pleasing habit which, whether as a warning or an inspiration, modern poets might do well to imitate. She carried an enormous diary under her arm; and in her mind several alternative ways of putting down her reflections on her way to the Palace.

“Good morning, dear Countess,” said the King, rising only too gladly from his nibs; “an early visit.”

“You don’t mind, your Majesty?” said the Countess anxiously. “There was a point in our conversation yesterday about which I was not quite certain——”

“What were we talking about yesterday?”

“Oh, your Majesty,” said the Countess, “affairs of state,” and she gave him that wicked, innocent, impudent, and entirely scandalous look which he never could resist, and you couldn’t either for that matter.

“Affairs of state, of course,” smiled the King.

“Why, I made a special note of it in my diary.”

She laid down the enormous volume and turned lightly over the pages.

“Here we are! ‘Thursday. His Majesty did me the honour to consult me about the future of his daughter, the Princess Hyacinth. Remained to tea and was very——’ I can’t quite make this word out.”

“Let me look,” said the King, his rubicund face becoming yet more rubicund. “It looks like ‘charming,'” he said casually.

“Fancy!” said Belvane. “Fancy my writing that! I put down just what comes into my head at the time, you know.” She made a gesture with her hand indicative of some one who puts down just what comes into her head at the time, and returned to her diary. “‘Remained to tea, and was very charming. Mused afterwards on the mutability of life!'” She looked up at him with wide-open eyes. “I often muse when I’m alone,” she said.

The King still hovered over the diary.

“Have you any more entries like—like that last one? May I look?”

“Oh, your Majesty! I’m afraid it’s quite private.” She closed the book quickly.

“I just thought I saw some poetry,” said the King.

“Just a little ode to a favourite linnet. It wouldn’t interest your Majesty.”

“I adore poetry,” said the King, who had himself written a rhymed couplet which could be said either forwards or backwards, and in the latter position was useful for removing enchantments. According to the eminent historian, Roger Scurvilegs, it had some vogue in Euralia and went like this:

“Bo, boll, bill, bole.

Wo, woll, will, wole.”

A pleasing idea, temperately expressed.

The Countess, of course, was only pretending. Really she was longing to read it. “It’s quite a little thing,” she said.

“Hail to thee, blithe linnet,

Bird thou clearly art,

That from bush or in it

Pourest thy full heart!

And leads the feathered choir in song

Taking the treble part.”

“Beautiful,” said the King, and one must agree with him. Many years after, another poet called Shelley plagiarised the idea, but handled it in a more artificial, and, to my way of thinking, decidedly inferior manner.

“Was it a real bird?” said the King.

“An old favourite.”

“Was it pleased about it?”

“Alas, your Majesty, it died without hearing it.”

“Poor bird!” said his Majesty; “I think it would have liked it.”

Meanwhile Hyacinth, innocent of the nearness of a mother, remained on the castle walls and tried to get on with her breakfast. But she made little progress with it. After all, it is annoying continually to look up from your bacon, or whatever it is, and see a foreign monarch passing overhead. Eighteen more times the King of Barodia took Hyacinth in his stride. At the end of the performance, feeling rather giddy, she went down to her father.

She found him alone in the library, a foolish smile upon his face, but no sign of a letter to Barodia in front of him.

“Have you sent the Note yet?” she asked.

“Note? Note?” he said, bewildered, “what—oh, you mean the Stiff Note to the King of Barodia? I’m just planning it, my love. The exact shade of stiffness, combined with courtesy, is a little difficult to hit.”

“I shouldn’t be too courteous,” said Hyacinth; “he came over eighteen more times after you’d gone.”

“Eighteen, eighteen, eight—my dear, it’s outrageous.”

“I’ve never had such a crowded breakfast before.”

“It’s positively insulting, Hyacinth. This is no occasion for Notes. We will talk to him in a language that he will understand.”

And he went out to speak to the Captain of his Archers.